Feature

“It is foolish to think we could ever remove our dependence on China”

China has an edge over other countries in existing lithium refining capacity, and further investment in supply chains across Africa. Ashima Sharma asks if the world can keep up with lithium demand without China’s involvement.

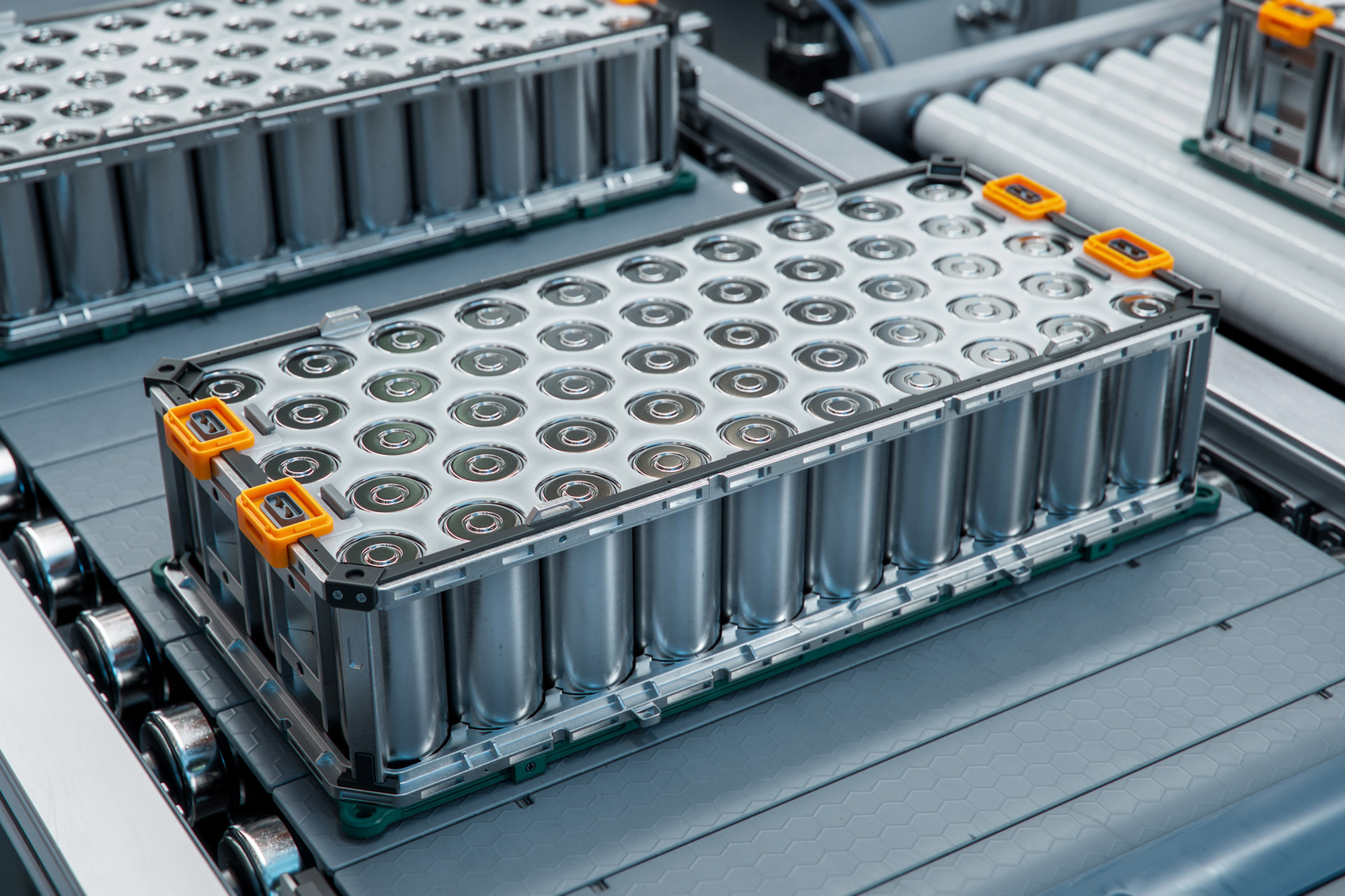

The global electric vehicle supply chain is heavily dependent on China’s lithium supply. Credit: IM Imagery via Shutterstock

“We are going to continue to remain dependent on China and I think the capital costs and economics are ultimately going to drive a lot of this,” Sarah Maryssael, chief strategy officer of global lithium technology company Livent, said while talking about the global electric vehicle (EV) supply chain at the 2023 FT Mining Summit in London.

While countries like the US and Australia are pouring in tax benefits and other domestic incentives to cut down on China’s dominance in the lithium supply chain, Maryssael adds, “the development of a supply chain outside of China, is what the West lacks”.

“We [the West] don’t build refineries and conversion capacities anymore, the way that we would once. It is foolish to think we could ever remove our dependence on China.”

China has 8% of the global lithium reserves and 72% of the world’s refining capacity as of 2022. Now, the country is fighting its mineral cold war by investing heavily in African countries. Already dominating the processing capacities for lithium used in the lithium-ion batteries for EVs, China is now taking control of mines in other countries by direct investment or ownership of subsidiaries.

Forecasts suggest that Chinese investment in mines across the African continent will increase the production of lithium raw material more than 30-fold by 2027. Africa could account for 12% of the global lithium supply, compared to 1% in 2022.

But Australia, Canada and the US, who hold some of the largest lithium as well as critical mineral reserves, have been blocking Chinese investment citing concerns over national security.

The US’s initiative to reduce dependence on China started with the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022 that offers companies hundreds of billions of dollars in tax breaks to make clean technologies in the US. Following suit, the EU, under its green deal industrial plan, also announced a target to make 40% of “strategic net zero technologies” within its borders by 2030.

However, China dominates each step in the production of a lithium-ion battery, a key component in EVs. EVs use six times more rare minerals than conventional cars because of their batteries. Currently, China, either by domestic mining or acquiring stakes in mining companies globally, controls 41% of the world’s cobalt and most of the mining of lithium. Approximately 67% of global lithium supply is processed by China, along with 73% of cobalt, 70% of graphite and 95% of manganese, all critical minerals for green technologies.

By 2025, research suggests, China could control up to one third of the world’s lithium. With US and the Europe motivated to cull dependence of China, the question remains- is it possible?

Controlling supply in Africa

By July 2023, China had established an early mover advantage in Africa’s lithium supply chain. In March 2023, Africa’s first Chinese-owned lithium concentrate plant started trial production in Zimbabwe. China-based battery minerals producer Huayou Cobalt, one of the world’s largest cobalt producers, acquired the Zimbabwean mine for $422m. The company said it would spend $300m to build a plant to process 4.5 million tonnes of lithium ore. The mine is expected to produce 50,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent lithium concentrate.

Shortly after, Huayou also announced an investment of $1.67m in Askari metals, an Australian listed company, to advance its exploration of the Uis lithium project in Namibia. Huayou’s presence in Africa extends to the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the company produces 100,000 tonnes of cathode copper and 10,000 tonnes of cobalt, both metals key to the energy transition.

The motive behind China's aggressive pursuit of African lithium reserves is multifaceted.

By June, one of the world’s 10 largest battery manufacturers, Gotion High Tech, a China-based manufacturer of lithium-ion power batteries, announced a memorandum of understanding with the Kingdom of Morocco to invest $6.4bn and establish a new 100 gigawatt-hour electric vehicle battery manufacturing facility in Morocco.

The motive behind China's aggressive pursuit of African lithium reserves is multifaceted. Geopolitically, China's aim appears twofold: securing a continuous and substantial supply of lithium while also asserting influence in resource-rich African nations. By investing heavily in these countries, Beijing solidifies its economic ties, and potentially reduces reliance on other lithium-rich regions where geopolitical tensions or other big competitors already exist.

Beyond raw material

Evidently, China’s grip extends beyond procuring raw material to downstream in the electric vehicle battery supply chain. With the US and the EU in constant geopolitical tussle with China, it leaves the countries with little time discover and develop lithium deposits.

In February 2023, the European Parliament voted to approve a new law that would ban the sale of new petrol and diesel cars by 2035. Independent carmakers in the US have also suggested 2035 as their deadline to go all-electric. The race to compete with the Chinese industry has sent car companies like Ford and General Motors scrambling for resources and showing up to deal directly with mining companies in Argentina, Chile and Quebec.

US-based General Motors now has deals with Livent, a lithium company that will procure lithium from its South American operations. It has further invested $650m in Vancouver-based Lithium Americas. Similarly, Ford has signed long term lithium agreement with Chilean supplier SQM. Rio Tinto, one of the largest mining players, has also agreed to supply lithium to Ford from a mine it is developing in Argentina.

The late entry in investing into the development of supply chains is likely to leave US automakers paying significantly more than the metal’s worth.

The late entry in investing into the development of supply chains is likely to leave US automakers paying significantly more than the metal’s worth. Tesla, which has consistently built a supply chain for lithium and other raw materials - 40% of which are sourced from China - has gained a strong foothold in the market share of China, Europe and the US.

While China expands its presence in African countries, it has also partnered with countries like Bolivia in South America. Western players have steered clear of the country for its political instability, but China, with its grip in the business, isn’t afraid to make a steep $1.4bn investment in two lithium projects managed by Chinese battery maker CATL.

Will the lithium market remain favourable for China?

China may have mastered a steady supply chain, but market forces have hit it where it hurts: prices. Firstly, the demand for EVs did not pick up at the anticipated rate in 2023 after the Chinese government ended a decade-long state subsidy on the purchase of EVs. This scuttled the demand for lithium carbonate used in EV batteries, causing the price to fall by 77%.

Furthermore, in December 2023, the spot price of lithium fell to a two-year low. As global production of the metal continues to grow, it is anticipated to fall further through 2024. While a fall in price affects miners, it is likely to benefit EV manufacturers through low procurement rates.

However, in the race for going green and electric, lithium-ion batteries are not the only player. Increasingly, research has delivered on the effectiveness of sodium-ion batteries and other alternatives such as using copper instead of aluminium.

Sweden based Northvolt has already made a breakthrough in sodium-ion battery technology, said to be more cost-effective and sustainable than conventional nickel, manganese and cobalt or iron phosphate chemistries, principally because the minerals it uses, such as sodium and iron, are abundantly available.

Northvolt’s current sodium-ion batteries are designed for use in energy storage, but subsequent generations with higher energy density could eventually be used in electric vehicles.

On the question of weaning dependence off China for EVs, it turns out lithium is not the only factor of concern. Supply chains for other critical miners are either well established or give China the advantage of geography.

China also has massive refining capacity for nickel, graphite, cobalt, manganese, the technical prowess of making batteries, and an already established market share manufacturing 54% of the world’s electric cars, giving the country a leap where others are starting out.