Feature

Endless expansion: how will China’s coal investments affect its energy mix?

Permitting of new coal power plants accelerated dramatically in China in 2022, according to new analysis. Isabeau van Halm asks how this will affect emissions.

Industrial operations in China. Credit: humphery via Shutterstock

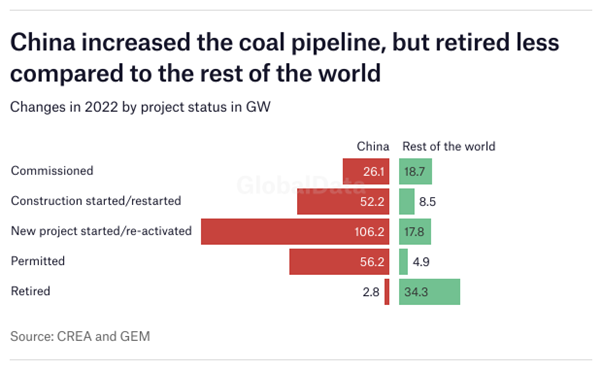

In 2022, permits for new coal power plants in China reached their highest level since 2015, according to a report from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), a think tank, and NGO Global Energy Monitor (GEM). Local governments approved permits for 106GW of new coal-fired power capacity last year, signalling the intent of local authorities to continue China’s push towards greater coal production, seeming to work in tandem with the priorities of the central government.

The report also reveals that more than 50GW of coal power capacity started and restarted construction in 2022, more than 50% more than the year before. In total, the coal power capacity starting construction in China was six times larger than the rest of the world combined.

New coal power capacity added to the grid in 2022 was steady compared with 2021 , with the total capacity added increasing from 26.2GW to 26.8GW between the two years, but researchers expect an increase in a few years when the newly permitted power projects come online. With many companies and governments around the world increasingly hesitant to invest in large-scale coal facilities, China’s mining and power sectors are a stark and unique contrast, that leave many questions as to the future of the country’s energy mix.

“The glaring exception”

“China continues to be the glaring exception to the ongoing global decline in coal plant development,” said Flora Champenois, research analyst at GEM, in a press release. “The speed at which projects progressed through permitting to construction in 2022 was extraordinary, with many projects sprouting up, gaining permits, obtaining financing and breaking ground apparently in a matter of months.”

China is the world’s biggest carbon emitter. Chinese President Xi Jinping has said the country will strive to achieve peak emissions before 2030 and be carbon neutral by 2060, but its coal expansion is at odds with the need to phase out fossil fuels to reach that goal. The International Energy Agency warned almost two years ago that global net-zero means there can be no new oil, gas or coal development.

A similar analysis of GEM data by think tank E3G shows that while on a global level, the new coal pipeline has reached historic lows, China’s coal plans threaten the progress towards net-zero.

“Almost every country and region in the world has stopped planning new coal power stations and many have now cancelled all remaining projects. This is a huge step towards keeping global heating below 1.5°C,” said Leo Roberts, programme lead at E3G, in a press release. “Unfortunately, a renewed coal boom in China is sending it off on a diverging pathway from the rest of the world, at potentially massive cost to the climate, and to China itself.”

According to the E3G analysis, China is now responsible for 72% of global planned coal capacity, which has increased compared to half a year ago, when the country accounted for 66%.

More coal, fewer emissions?

Yet the upswell in coal power development does not necessarily mean that the use of coal or even emissions from coal production will increase, as China is also investing heavily in renewables. If its clean energy capacity grows as planned and there is no sudden uptick in demand, extra coal power generation might not be necessary.

“The intention of the government is to start reducing coal consumption overall after 2025, which is when these plants would come online,” says Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at CREA. “The government’s plan is to reduce coal-fired power generation while increasing [coal] power plant capacity, meaning that the utilisation rate of the plants will fall.

The average utilisation rate of coal plants in China is currently just over 50%, which is already low.

“The average utilisation rate of coal plants in China is currently just over 50%, which is already low," he adds. In his eyes, investing in new coal plants today is "at the very least, economically more wasteful than shifting investments to clean solutions now".

China accounted for $546bn of energy transition investments in 2022, nearly half of the global total, according to a report from the research company BloombergNEF. These investments mean that China could be on track to start reducing coal consumption after 2025 or even sooner, suggests Myllyvirta. However, analysts worry that if all the newly permitted plants come online, both the government and power companies will push to continue using coal.

“China's targeted rate of emissions reductions after [a peak by 2030] is an open question and these kinds of vested interests make it harder to arrive at ambitious targets,” says Myllyvirta.

Safety concerns remain

Meanwhile, there are growing concerns that China’s coal investments will lead not only to long-term environmental damage, but pose short-term risks to the health of its coal miners. In February this year, a deadly coal mine collapse in the town of Alxa League in Inner Mongolia, northern China, left at least six people dead and almost 50 missing.

Inner Mongolia is the second-largest coal-producing province in China, and events such as these are concerning indications of the direction of Chinese coal. The cause of the collapse at the open-pit mine is still unknown, and the Chinese government has launched an investigation and sent working groups to supervise and inspect mines.

The collapse was just the latest in a string of deadly accidents. In 2022, 168 coal mining accidents caused the deaths of 245 people, according to the Chinese National Mine Safety Administration (CNMSA). It’s the highest death toll in years, and significantly higher than the year before when 91 accidents caused 178 deaths.

In a review of ten mine accidents in 2021, the CNMSA wrote that “the situation of mine safety production is still complex and severe” and that “the safety foundation is weak, and the supervision and supervision capabilities are still insufficient”. The increased accidents in the coal mining industry coincide with the government pushing for more coal production. The Alxa League mine had halted production for three years, but restarted in April 2021, reported Reuters.

Delivering energy security

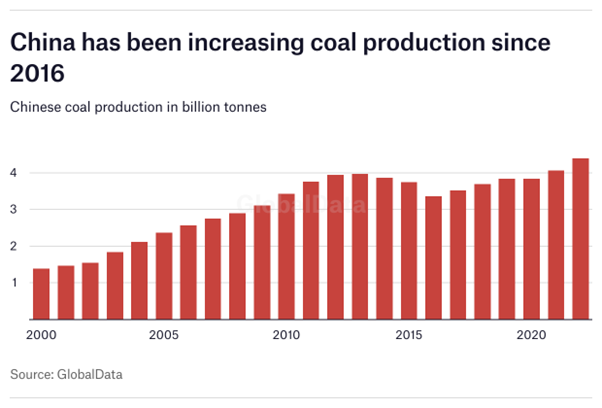

China is currently the largest global coal producer and consumer. According to data from GlobalData, China produced around 4.4 billion tonnes of coal in 2022, almost 8% more than the year before, and these figures are as likely to grow as they are to decline.

Shortly after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, coal imports surged, driven by concerns about energy security. China believes its energy security depends in part on coal, meaning that coal mining and the development of coal power plants are expected to remain priorities for the near future.

China believes its energy security depends in part on coal, meaning that coal mining and the development of coal power plants are expected to remain priorities for the near future.

At the beginning of the annual National People’s Congress, China highlighted the importance of coal for energy security, following not just soaring global energy prices, but also power shortages the country faced in the summer of 2022. While the government emphasised that China would keep investing in renewables to make climate mitigation targets, coal will retain a core of energy infrastructure and in 2023 research and development will focus on advanced and clean coal.

However, the country’s plan to ensure energy security through more coal production and capacity is “an illusion”, according to E3G.

“As the world turns its back on coal, China has little to gain from clinging to the dirtiest of fossil fuels,” said Belinda Schäpe, policy advisor at E3G. “As a responsible power, China can showcase its commitment to tackling climate change and the green transition: leading by example.”

A version of this article first appeared in our sibling publication Energy Monitor.