Deep-sea Mining

Stumbling towards the last frontier: greater hesitancy for deep-sea mining

Greenpeace, the WWF and other environmental organisations were already calling for a global mortarium on deep-sea mining. Now, as Isabeau Van Halm writes, governments are joining them.

A

t COP27, French president Emmanuel Macron called for an international ban on deep-sea mining. That same week, French ambassador Olivier Guyonvarch formally proposed a ban during a council meeting of the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

“As the effects of climate change become increasingly threatening and the erosion of biodiversity continues to accelerate, today it does not seem reasonable to hastily launch a new project, that of deep seabed mining, the environmental impacts of which are not yet known and may be significant for such ancient ecosystems which have a very delicate equilibrium,” Guyonvarch said at the ISA meeting in Jamaica.

The French Government is just the latest to demand a moratorium on deep-sea mining. Germany, Spain, Costa Rica, New Zealand, Chile and others want to put a stop to the rush to the deep sea due to the lack of scientific research on the environmental impact mining could have. In a statement published on 7 November, Greenpeace France said that it welcomes Macron’s announcement.

The organisation has been actively campaigning against deep-sea mining since early 2021 when seabed mining gained momentum after Nauru, an island in Micronesia, triggered a clause that means ISA has to complete the regulations necessary to approve mining within two years.

Seabed mining tests are underway

Since its founding in 1994, the ISA has been obligated to “ensure the effective protection of the marine from harmful effects that may arise from deep-sea related activities”, but there are limits to its scope.

The ISA only has authority over international waters, but not territorial waters. Around 60% of the global seabed lies beyond national jurisdiction, according to non-profit The Pew Charitable Trusts.

What makes the current opposition of governments stand out is that many are members of the ISA council, the executive branch of the authority, meaning their objections could have an impact on waters not typically covered by the ISA.

Yet, so far, there are no sufficient regulations or guidelines in place for mining the seabed. Negotiations in August ended without any agreements, and with just a few months before the two-year deadline passes, mining could start without environmental regulations in place.

Nauru sponsored a subsidiary of Canadian firm The Metals Company (TMC) to carry out deep seabed mining in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, an area that spans 4.5 million square kilometres in the Pacific Ocean. TMC intends to apply for an exploitation license in 2023, and if granted, would begin mining operations in late 2024.

In September, the ISA approved TMC to start a mining test. At the end of November, Greenpeace activists from Mexico and Aotearoa confronted the ship, the Hidden Gem, when it returned after the eight-week trial run. The ship carried back an estimated 4,500 tonnes of mineral-rich polymetallic nodules, according to shipping company Allseas, which called it a “record haul”.

“We are here today because deep sea mining threatens the health of the ocean and the lives and livelihoods of all who depend on it,” said James Hita, a campaigner from Aotearoa. “The ocean is home to over 50% of life on Earth and one of our biggest allies in fighting the climate crisis. We will not stand by while mining companies begin to plunder the seafloor for profit.”

Why the rush for deep-sea minerals?

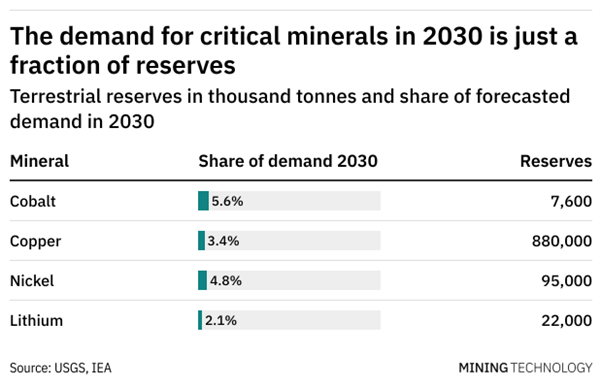

The world has been scrambling to find the minerals necessary for the energy transition. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), “clean energy technologies are becoming the fastest-growing segment of demand” for critical minerals. The organisation estimates that the clean energy sector’s demand for copper and rare earth elements will rise by more than 40% in the next two decades, more than 60% for nickel and cobalt and almost 90% for lithium. Production is struggling to keep up with the rising demand.

Most of those critical minerals, however, can be found in polymetallic nodules on the ocean floor – most notably copper, nickel, cobalt and manganese. These potato-shaped mineral concretions were first discovered during the voyage of the HMS Challenger in 1873 and contain high concentrations of several minerals, formed over millions of years. Because they lay on the ocean floor unattached, the process of collection can be relatively simple as it does not require large-scale drilling work.

According to the IEA, there are no signs of shortages when it comes to the amount of available resources. There are plenty of reserves for most minerals, with, for instance, 880 million tonnes of copper reserves on land and 95 million tonnes of nickel reserves, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

However, the IEA notes that there are concerns about the quality of these reserves. The declining quality of land-based minerals makes high-quality seafloor minerals attractive for exploration. For cobalt, for instance, the USGS estimates that around 120 million tonnes of cobalt resources can be found in the deep sea, compared to 7.6 million tonnes on land.

TMC argues that deep seabed mining is essential to get the critical minerals needed for the transition away from fossil fuels and that they are “the cleanest path toward electric vehicles”. The company eventually aims to extract 1.3 million tonnes of wet nodules per year and believes that mining its contract areas would result in enough minerals for 280 million electric vehicles.

Yet, some big automakers have aligned with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). BMW and Volvo, along with Samsung and Google, pledged in March 2021 “not to source any minerals from the deep sea and to refrain from using mineral resources from the deep sea in their supply chains and not to finance deep-sea mining activities”. Since then, Volkswagen, Scania, Renault and Rivian have joined the call for a moratorium on deep seabed mining.

Key to green transition, or environmental disaster?

While TMC says seabed mining would be preferable over mining on land because the mining of nodules generates no tailings leaves nearly no solid waste streams behind and does not contribute to deforestation, researchers say there are too many unknowns to determine the exact impact of deep-sea mining.

Scientists from a European research project that monitored the impact of seabed mining noted that even impacts from small-scale experimental seafloor disturbances had long-lasting effects and affected numerous ecosystems. They also concluded that the impacted area will be larger than just the mines area.

However, even with such research, the precise impact and exactly how long it would last are still not clear. As oceanographer Paul Snelgrove said: “We know more about the surface of the moon and Mars than we do about the deep-sea floor”.

We know more about the surface of the moon and Mars than we do about the deep-sea floor.

A literature review published in Marine Policy in April 2022 concluded that despite an increase in deep-sea research, the available research is still not comprehensive enough to be able to make well-informed decisions on deep-sea mining and that at least a decade of more research is needed. This lack of information was a key driving force behind a drive that has called for a pause in the race to the bottom of the ocean, with more than 650 marine experts signing a statement to this effect.

“Deep-sea ecosystems are currently under stress from a number of anthropogenic stressors including climate change, bottom trawling and pollution,” reads the statement. “Deep-sea mining would add to these stressors, resulting in the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning that would be irreversible on multi-generational timescales.”

The statement continues: “Without this information, the potential risks of deep-sea mining to deep-ocean biodiversity, ecosystems and functioning, as well as human well-being, cannot be fully understood.”

Preventing ‘serious harm’ to the seabed

There have been concerns about the motivations of the ISA itself. The body benefits from the revenue received from mining licenses, resulting in the UK House of Commons already expressing concerns in 2019 about this “clear conflict of interest”. The ISA has also faced accusations of failing to be transparent after it did not renew a contract with an independent reporting service in April 2022.

When the ISA permitted a mining trial in September, this came as a surprise, according to the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, an alliance of over 100 international organisations working to promote the conservation of biodiversity on the high seas.

A New York Times investigation in August 2022 revealed how the ISA gave key information to TMC, giving the company an edge and even setting aside the most valuable mining sites for the company’s future use.

Sufficient research will be needed before mining projects in the deep sea can start, as well as an evaluation of the duties of the ISA that are needed to create a coherent mining code.

Sufficient research will be needed before mining projects in the deep sea can start, as well as an evaluation of the duties of the ISA that are needed to create a coherent mining code. The authority is developing regulations based on the obligation that it must prevent serious harm, but defining what ’serious harm’ entails is critical to effective regulation.

Another study from December 2021, which looks at key outstanding matters that need to be resolved for the ISA’s mining code, says there are still a significant number of outstanding matters that need to be discussed before the July 2023 deadline. It advises that rushing to finalise the code without addressing all outstanding matters could “lead to very problematic outcomes”, as it would be difficult to make changes once the first project is granted permission.

Author Pradeep Singh concludes: “Once the regulations are in place and the first exploitation applications are subsequently approved, it would be hard for the ISA to preclude further applications or rollback the conduct of exploitation activities.”

// Main image: Hand by beach shells. Credit: Wdnld via Shutterstock