Feature

Uranium as a critical mineral: how counties are mitigating supply chain risk

With interest in nuclear power on the rise, many countries are keen to secure supplies of nuclear fuel. Kit Million Ross asks whether classifying uranium as a critical mineral could be the answer.

Many countries are keen to secure supplies of nuclear fuel.

When we talk about minerals that are essential for our modern world, uranium often finds itself in the spotlight. As the world turns its attentions towards nuclear power as a shortcut to a low-carbon future, especially as low-carbon hydrogen rises in popularity, the need for consistent sources of uranium is becoming ever clearer.

But is classifying uranium as a critical mineral the answer?

Japan says ‘yes’

Japan has had something of a rocky relationship with nuclear power, to put it mildly. Until 2011, when a tsunami caused an accident at Fukushima nuclear power plant that leaked radioactive material into the surrounding area, the country produced around 30% of its power from nuclear sources.

This figure was expected to increase 40% by 2018, but in the years following the accident has plummeted to around 4%. The World Nuclear Society states that the nation is aiming to have 20% of its power coming from nuclear energy by 2030, as hesitancy over nuclear energy begins to ease.

With more and more nuclear reactors coming back online in Japan each year increasing demand for uranium, and with Japan already being the world’s third-largest producer of uranium after the US and China, the nation recognises the vital importance of uranium. As such, in February 2023, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) officially placed uranium on its list of critical minerals.

While Japan currently consumes vast amounts of uranium, it has no domestic production and relies entirely on imports. That isn’t to say Japan has no reserves of uranium. Far from it – METI estimates that Japan has 6,600 tonnes of uranium reserves. While this is only enough to meet Japan’s internal demand for about six years, it could certainly help support the nation to rely less on imports.

Japan’s decision to label uranium as a critical mineral encourages the country to fund domestic exploration and extraction, as well as to focus more attention on a steady supply of the element.

America says ‘no’

Not all countries agree that uranium should be a critical mineral, though.

In the US, designation of critical minerals is decided by the US Geological Survey (USGS), alongside the US Department of Energy. Despite being the world’s largest consumer of uranium, the US declined to include uranium as a critical mineral on its Final 2023 Critical Materials List, making it the only material labelled as “critical” or “near critical” to not make the cut.

The reasoning behind this highlights an interesting quirk in US definitions of criticality; the Energy Act of 2020 defines critical materials as “any non-fuel mineral, element, substance, or material.”. Given uranium’s most prominent use is as fuel in nuclear reactors, it did not qualify for the listing.

Has Australia got it right?

Although each country has a different definition of critical minerals, one of the clearest definitions comes from Geoscience Australia, which defines a critical mineral as “a metallic or non-metallic element that has two characteristics: (1) It is essential for the functioning of our modern technologies, economies or national security and (2) There is a risk that its supply chains could be disrupted”.

By this definition, uranium’s exclusion from Australia’s critical minerals list makes sense, as the nation produces vast quantities of uranium but, with no nuclear power plants, exports all of it. Using Australia’s definition as a reference, Japan’s inclusion of uranium as a critical mineral is logical, given it imports all of its supply and has increasing numbers of nuclear power plants and thus increasing need for uranium.

Although the American definition of a critical mineral excludes uranium as it is used almost exclusively as a fuel, it could be argued that this definition needs to change, as the US generates 19% of its power from nuclear sources, meaning that any major disruption in the supply chain could cause an enormous issue for the US electricity grid, which is already famed for being shaky and inflexible. But how much of a risk is there to the supply chain?

Geopolitical considerations

Recent geopolitical tensions and trade dynamics have highlighted the strategic importance of securing domestic sources of uranium, or at least ensuring a diverse range of international sources.

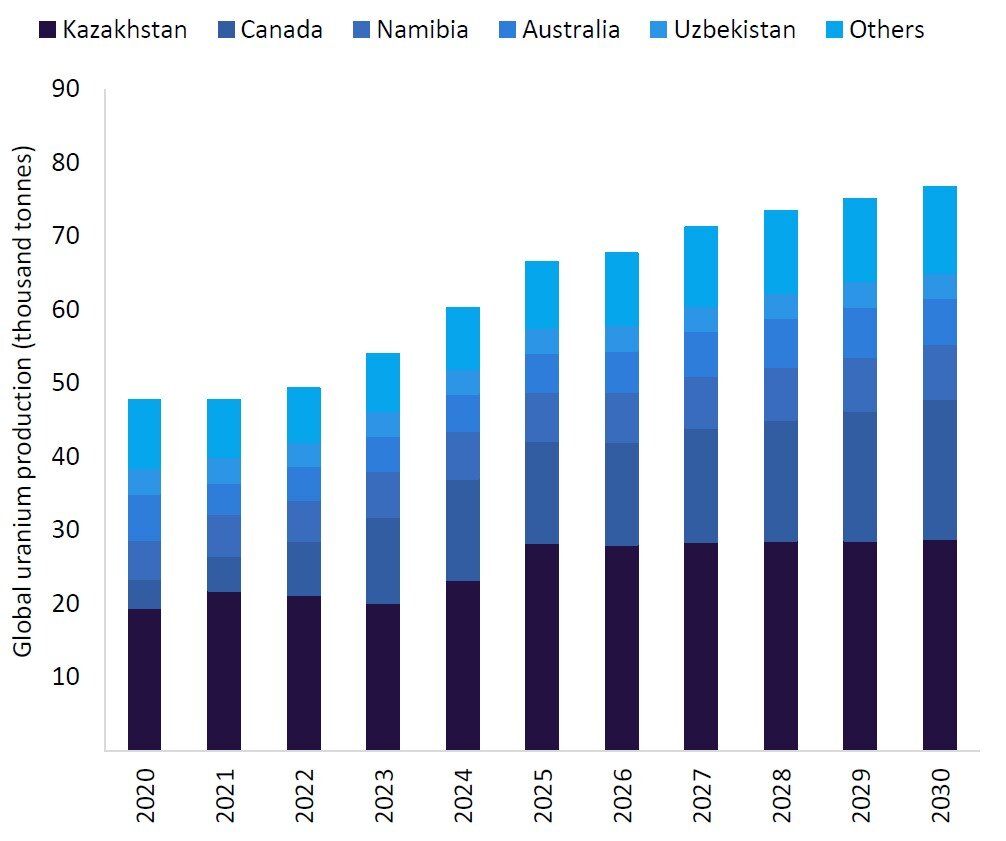

The difficulty here is that uranium production is clustered very strongly in a few nations; namely, Canada, Kazahstan and Nambia, which, according to GlobalData’s Uranium Mining to 2030 report, collectively produced 70% of the world’s uranium in 2023. Another 15% was made up by production from Australia and Uzbekistan, meaning that 85% of global uranium supply came from just five nations.

Global uranium production by country. Source: GlobalData, World Nuclear Association

With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and more recently the war in Gaza, world leaders have become aware of just how quickly geopolitical relationships can deteriorate, and the impact this can have on global supply chains.

Uranium prices skyrocketed by as much as 40% mere weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine, even though, according to MarketWatch, “the war has had little immediate impact on global supplies of the fuel”. This has highlighted just how unstable any global conflict can make the uranium market and given nations motivation to diversify their uranium supply chains and reduce dependence on politically unstable regions.

Classifying uranium as a critical mineral could incentivise investments in exploration, mining, and processing facilities within national borders.

The bottom line

Should uranium be classified as a critical mineral? It's a question without a simple answer, and the implications span energy security, geopolitics, environmental sustainability, and technological innovation. While recognising the strategic importance of uranium, policymakers must carefully weigh the trade-offs.

Ultimately, the classification of uranium as a critical mineral is one that can’t be made on a global scale, as it is unique to any given nation’s need for uranium and ability to produce it domestically. What is clear is that uranium is becoming ever more important, and its supply and demand is something that all nations should take seriously.