Feature

Electrification: do we have the goods?

The push for electrification and a green future is putting immense demand on critical mineral mining. But does the earth physically have enough material to meet our needs? Kit Million Ross digs deep.

Electric car lithium battery pack and wiring connections. Credit: Smile Fight/Shutterstock.

In an era dominated by the pursuit of sustainable energy solutions, the spotlight is undeniably on electrification. As the global demand for electric vehicles, renewable energy sources, and high-tech gadgets continues to surge, a pressing question emerges from the depths of our technological progress: Do we have enough critical minerals to power this electrified future?

In this exploration, we delve into the intricate web of minerals that underpin our electrified world, unravelling the challenges and uncertainties surrounding their supply, and contemplating the sustainability of our relentless march towards a greener, electrified tomorrow.

With Australia being the world’s largest lithium producer, and with lithium ion-batteries being the leading battery technology for battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and the subject of fervent discussion throughout 2023, we’ll be holding a microscope up to lithium to see what lessons we can apply to other critical minerals used in battery technology.

She’s electric: EV demand is soaring

Arguably the biggest driver of the demand for battery metals is the skyrocketing popularity of electric vehicles (EVs). Many countries are bringing in bans on the sale of new combustion engine cars, with the UK government announcing in 2020 that new non-plug-in vehicles would be banned by 2030, with Sweden announcing a similar ban and Norway confirming it will introduce its ban on new petrol cars by 2025.

Incoming legislation like this is driving up EV sales massively and causing immense demand for lithium: GlobalData’s Electric Vehicles Market 2023 report notes that “demand for lithium due to increased battery sales is on track to grow by more than 400% from 2020 to 2030, so there is intense pressure to mine lithium fast enough to secure long-term supply deals in a volatile market”.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global EV sales hit 10.6 million units in 2022, a figure that is expected to more than double to reach 22.1 million units by 2025 and 40.2 million units by 2030.

Taking stock

According to the US Geological Survey (USGS), global lithium reserves totalled 26.0 million tonnes as of January 2023. Chile has the largest lithium reserves by far, with 9.3 million tonnes of lithium held in its reserves. It’s not entirely surprising that Chile holds the record for largest lithium deposit per nation – it makes up part of the South American “lithium triangle” alongside Argentina, which itself holds third place in the global lithium charts with 2.7 million tonnes of lithium, and Bolivia.

While Bolivia does not chart in the top eight of global lithium reserves, it does have the top global level of lithium resources at 21.0 million tonnes; however, by definition as a mineral reserve, it is unclear how much of this total is economically viable to mine.

Australia, meanwhile,holds the world’s second-largest levels of lithium reserves, with 6.2 million tons as of January 2023 – an amount that represents 23.8% of total global lithium reserves. Western Australia’s lithium deposits are recognised as having high economic concentrations of lithium, with Greenbushes Lithium Operations particularly notable as a high-grade lithium deposit.

Caption. Credit:

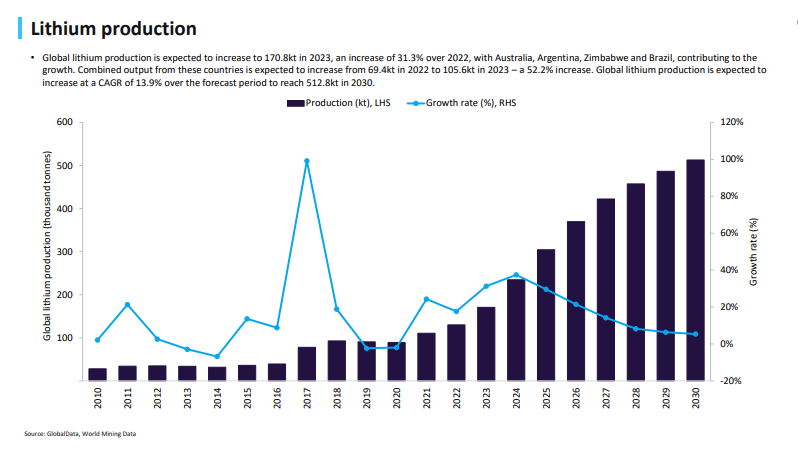

According to GlobalData’s Global Lithium Mining to 2030 report, lithium production is expected to reach 512.8 kilotons by 2030 – the year for which many countries have set their net-zero deadline.

’Please sir, can I have some more?’

According to GlobalData’s Electric Vehicles Market 2023 report, “the EV industry’s single biggest concern is securing supplies of key minerals and rare earths to feed the swelling population of battery cell gigafactories needed to supply a possible four-fold growth in demand for lithium batteries by 2030”.

This isn’t merely a short-term concern, although delays in approving new mining projects are causing supply chain issues for lithium around the world, but an issue that could reach a crisis point if it becomes uneconomical – or even physically impossible - to mine new lithium in the future. As the report notes, in the future, “unsecured [lithium] supplies may be hard to come by as the capacity to mine new high-grade lithium fails to keep up with demand”.

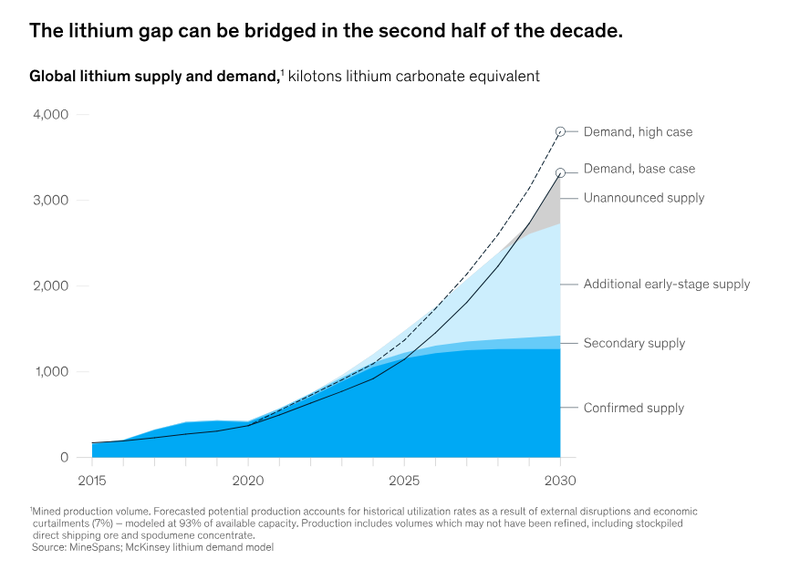

Analysis of lithium markets by McKinsey predicts that batteries will account for 95% of global lithium demand by 2030, with total lithium demand growing annually by around 25% over that period. This report remains optimistic that global supply can meet demand for years to come, but should we be considering a longer-term view of the future of this finite resource?

Caption. Credit:

‘Let’s go round again’: lithium recycling as a future-proof solution

McKinsey’s analysis predicts that by 2030, recycling could account for up to 6% of global lithium supply. While the current market for lithium battery recycling remains small, companies such as Finland’s Fortum Battery Recycling are attempting to make the most use out of critical minerals found in batteries and prevent batteries from going to landfill. At its material recycling facility in Harjavalta, Finland, Fortum is able to recover the vast majority of the critical minerals used in EV batteries using a low-emissions process.

“With our new low CO2 hydrometallurgical plant in Harjavalta, we are able to sustainably produce the materials urgently needed for new EV lithium-ion and industrial-use batteries,” says Tero Holländer, head of business line for batteries at Fortum Battery Recycling. “Thanks to our cutting-edge hydrometallurgical technology, 95% of the valuable and critical metals from battery's black mass can be recovered and returned to the cycle for the production of new lithium-ion battery chemicals.”

Recycling battery minerals may have another unforeseen advantage. A 2022 report published in Scientific American has shown that certain battery recycling methods may produce batteries that charge faster than the original batteries they were recycled from – an exciting prospect for future battery technology.

With the potential environmental, cost, and technological benefits to recycling lithium-ion batteries, it is baffling that recycling rates are so low. A study found that less than 1% of lithium-ion batteries are recycled in the US and EU, shockingly low volumes when the demand and price of lithium remain so high.

So what now?

As we navigate the path ahead, the electrified world stands at a crossroads, balancing the promise of innovation with the responsibility of resource stewardship.

The challenge is clear: Can we electrify our future without draining the very elements that power it? The answer lies not only in the depths of lithium mines but in our collective commitment to sustainable practices, responsible mining, and the pursuit of alternative solutions to secure the longevity of our electrified journey.