ESG

Paying for the past: how long can a miner be held responsible?

Holding individuals and companies responsible for their historical actions is a subject of contention, perfectly illustrated by legal action being taken against Anglo American for one of its former mines in Zambia. Andrew Tunnicliffe talks with Richard Meeran and Zanele Mbuyisa about the case and the fairness of seeking reparations for the ills of the past.

"A

s charities, governments and organisations around the world continue to confront and redress the darker periods of their histories, we believe the time has come for mining companies to be held to the same standards.”

It’s a powerful statement that will no doubt raise eyebrows among the world’s leading mining companies. “After all, it’s the very standards they claim they are already setting themselves,” continues Richard Meeran, partner and head of the International Department at specialist human rights law firm Leigh Day.

Meeran was speaking in broad terms about the role mining companies play in the world today, the actions they’ve taken in the past and the impacts those actions have had on the communities and the environments in which they operate. In October 2020 Leigh Day and Mbuyisa Moleele, a public interest and civil litigation law specialists, filed a class action lawsuit against Anglo American South Africa Limited (AASA), which could set a precedent for future rulings on the responsibilities of mining companies.

A class action lawsuit

The action is on behalf of an estimated 100,000 individuals in the Kabwe District of Zambia believed to have been poisoned by lead. Both firms say the application was brought by 13 representatives on behalf of children under 18, and girls and women who have been, or may become pregnant in the future. They believe the facility, known as Broken Hill mine, had a detrimental impact on local people through the contamination of the local environment while under the control of AASA, a subsidiary of Anglo American.

Kabwe was home to the lead mine operated by the Anglo American group from 1925 to 1974, when ownership was nationalised under the Zambian Consolidated Copper Mines (ZCCM) before being placed under care and maintenance in 1994.

Most of the lead currently in the local environment and which poses health risks to the community today is likely to have been deposited between 1925 and 1974.

However, a partner at Mbuyisa Moleele, Zanele Mbuyisa ,says: “According to experts, most of the lead currently in the local environment and which poses health risks to the community today is likely to have been deposited between 1925 and 1974.”

“Children of Kabwe”, the campaign surrounding the lawsuit, aims to compensate children and women under 50 who may become pregnant in the future and whose children are likely to be affected by lead poisoning, to establish a blood lead level screening system for children and pregnant women, and to cover the costs for remediation of the area to ensure the health of future generations is not jeopardised.

A case to answer?

However, it’s a case that has raised questions about the legitimacy of holding today’s Anglo American executives accountable for the actions of their predecessors and the impacts they had. For Meeran and Mbuyisa, the answer is simple; they say the damage done was under ASSA’s management and the impacts were known to them at that time.

A 1969–70 study of 500 local children concluded children had significant levels of lead in their bodies. The report, compiled by then Kabwe mine physician Dr Ian Lawrence – who has since provided testimony in the case – was passed to Anglo American at the time.

“Measures required to stop lead emissions and decontaminate the land were not taken and operations were passed to ZCCM in 1974,” says Meeran. “Consequently, Anglo American has been well aware for at least the past 50 years that its Kabwe operations had caused, and would continue to cause, widespread serious lead poisoning of the local community.”

The impact of Anglo’s presence in Kabwe did not diminish when the company transferred the Kabwe mine to ZCCM in 1974.

As part of the legal actions, claimants’ representatives have argued that “AASA is liable for the harm because it played a key role in controlling, managing, supervising and advising on technical, medical and safety aspects of the operations of the mine, deficiencies which resulted in heavy contamination of the local environment with lead”, they say, and that “it [ASSA] knew, or ought to have known, of the lead poisoning of the local community that had and would be caused by its Kabwe operations”.

They conclude the company “failed to take measures to prevent and minimise lead poisoning of the community; additionally, AASA failed to ensure the clean-up of the communities’ contaminated land”.

Mbuyisa continues: “The impact of Anglo’s presence in Kabwe did not diminish when the company transferred the Kabwe mine to ZCCM in 1974.” Countering questions as to whether ASSA’s should still be held responsible decades on, Mbuyisa says: “It is important to note liability is not contingent on majority shareholding. It is alleged that AASA is liable because of its actual role in controlling, managing, supervising and advising on the technical, medical and safety aspects of the mine’s operations.”

// 3D System Model and Completed Installation. Credit: Deimos

Reparation and responsibility

Meeran adds that in any event, according to claimants’ experts, most of the lead currently in the local environment, in a form that poses a risk to the community, is likely to have been deposited during AASA’s stewardship. “AASA is a highly profitable corporation which benefitted financially from its operations in Kabwe,” he says.

“We call upon Anglo’s shareholders to urge the company to take responsibility for the Kabwe crisis – consistent with its Group Human Rights Policy, which makes commitments to respecting, upholding and advancing the human rights of the citizens in its areas of operation – and endorse the aims of the lawsuit.”

At the end of 2019 the Zambian Government began a programme of redress, funded by the World Bank and supported by the Japanese Government and UNICEF. Among its work the state has remediated homes and public buildings, introduced lead testing for individuals and headed a campaign to raise awareness of lead poisoning. The work, however, has received criticism from some, including Human Rights Watch, for lacking in scope and being too slow. The human rights advocate detailed a number of criticisms and demands on the government of Zambia under the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

// Main image: 3D System Model and Completed Installation. Credit: Deimos

We intend to defend our position as we don’t believe Anglo American is responsible for the current situation.

For its part, Anglo American denied any responsibility in the face of “mass poisoning” accusations. Speaking some time after the news broke of the legal action, the company’s Chief Executive Mark Cutifani said: “We intend to defend our position as we don’t believe Anglo American is responsible for the current situation.” His statement echoed a previous line taken by the multinational committing to “take all necessary steps to vigorously defend its position”.

Speaking with Reuters the miner added that it was one of several investors in the mine before it was nationalised. It added: “Furthermore, in the early 1970s the company that owned the mine was nationalised by the Government of Zambia and for more than 20 years thereafter the mine was operated by a state-owned body until its closure in 1994.”

In response Mbuyisa says: “Anglo’s refusal to take responsibility or action to address the ongoing damage to the health and environment of the Kabwe communities is inconsistent with publicly stated human rights commitments.”

Looking ahead

Together the law firms called on AASA to immediately establish and support blood lead screening, provide financial compensation and contribute to the clean up and remediation of the area to ensure the health of future generations. They also call on the company to “openly and honestly acknowledge the devastating legacy of its operations in Kabwe and long lasting damage to the health of the community.”

“An environmental and public health crisis of the magnitude of Kabwe’s would be considered a corporate scandal if it occurred in the UK or US,” says Meeran.

// Main image: 3D System Model and Completed Installation. Credit: Deimos

They also call on the company to ‘openly and honestly acknowledge the devastating legacy of its operations in Kabwe and long lasting damage to the health of the community.

He adds that in today’s mining sector, conversations concerning environmental, social and governance issues tend to place greatest emphasis on the environment, giving mining companies “license to ignore a history chequered by colonial indifference to the land and people most impacted by the mining industry”.

This, he says, is evidenced in the Kabwe case: “It serves as a stark illustration of what happened in the past when large multinational mining companies were effectively given free rein to exploit the resources and people in Southern Africa, with tragic human consequences.”

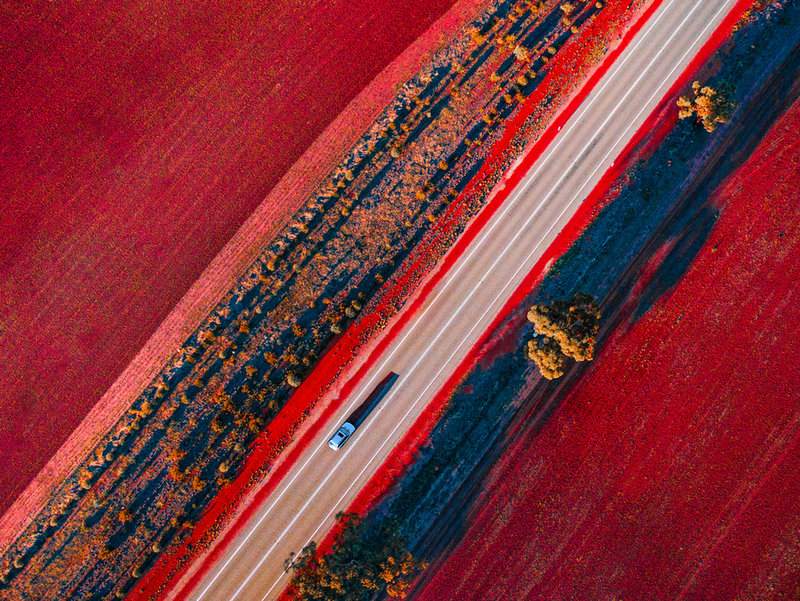

// Main image. Credit: Lawrence Thompson