Feature

Critical mineral recycling could avoid energy transition shortages

Technologies like batteries as well as those for renewables and hydrogen power generation depend on critical minerals. Stu Robarts finds out how recycling can support demand.

Lithium evaporation pools in Argentina. Credit: Freedom_wanted / Shutterstock

Supply-side demand challenges of mining critical minerals may impact the global pursuit of net zero, a new report suggests, but another has found that critical mineral recycling policies could mitigate such issues.

Over 70 countries have set net-zero targets, with more having pledged to lower their emissions, but the development of technologies like batteries as well as those for solar, wind, nuclear and hydrogen power generation depend on critical minerals.

The 2024 edition of GlobalData’s Critical Mineralsreport identifies 15 minerals that are important for the energy transition, with the five most critical being lithium, cobalt, copper, nickel and rare earth elements (REEs). It also identifies four key risks to the supply of those required.

The report states: “The rapid scale-up of clean energy technologies required to reduce carbon emissions depends upon the intensive mining of several minerals. The demand for these minerals will rise rapidly as the pace of the energy transition increases. The criticality of these minerals further depends upon a combination of supply chain risk factors, including their near-term depletion due to the decreasing ore grade, resource monopolisation, geopolitical tensions and environmental, social and governance considerations. With all these factors in place, there are concerns that shortages of critical minerals may disrupt international energy transition goals.”

While acknowledging such concerns, the IEA’s newly released Recycling of Critical Minerals: strategies to scale up recycling and urban mining report, has found that a surge in new policies and facilities to support the recycling of critical minerals “could significantly reduce potential strains on supply as countries pursue energy transitions.”

Critical mineral key risks

Of the accelerated demand for critical minerals, GlobalData’s report notes that there is a strain being put on existing mines, while new mines can take over ten years to develop and bring online. As such, it suggests there is the potential for a slowdown in the production of green technologies in the coming years, which in turn would likely delay emissions objectives. It adds: “Expanding adjacent industries, such as semiconductors, requires much of the same mineral resources, thus adding to global demands.”

As the report also outlines, many critical minerals are found in large concentrations within specific regions. “The uneven distribution of mineral resources has led to volatile market dynamics, which are vulnerable to sudden changes in export quotas and production volumes within these regions,” it says.

China, in particular, dominates the mineral processing sector, accounting for >90% of REEs, >70% of cobalt, ~65% of lithium, ~45% of copper and >25% of nickel. Such dominance becomes a geopolitical issue, with countries able to assert power over those dependent on their resources.

In relation to China specifically, the report says: “With enviable foresight, China acquired or secured long-term contracts with numerous mines worldwide. This has contributed positively to the vertical integration and development of China’s EV and energy transition industries. To curb China’s technological expansion, the US has imposed numerous well-publicised sanctions on China over the years, resulting in substantial disruption along the supply chain.”

Other geopolitical issues, such as conflicts, trade wars and questions of ethics and sustainability, also have ramifications for supply. The ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine, for example, has not only disrupted supply chains physically and by deterring investment due to elevated risk, but also through resulting sanctions. A raft of measures has been placed on Russia by the likes of the US and the EU as a result of its invasion of Ukraine, stifling trade and, in turn, the development of technologies.

Finally, the report notes that water scarcity is a growing issue for mining, as areas of the world endure drought more often and for longer. Water is essential for mineral extraction and processing, but the process can also exacerbate shortages where freshwater is already limited.

The report comments: “Already, several mines are exploiting seawater to make up the shortfall required for mining operations. However, using seawater may increase the operational cost of mineral production due to transportation costs and the requirement for seawater to be treated before use.”

Critical mineral recycling

Despite these potential disruptions to supply, the IEA has found that scaling up critical minerals recycling could “deliver major benefits for energy security, diversification and emissions reductions.” Its report suggests that the growth in new mining supply for critical minerals could be brought down by between 25% and 40% by mid-century by scaling up recycling.

While it says that the use of recycled materials has failed to keep pace with rising materials consumption, the report suggests there is “vast potential for expanding recycling worldwide, if the right policy incentives are in place”, and that indeed that policy interest in the area is on the up.

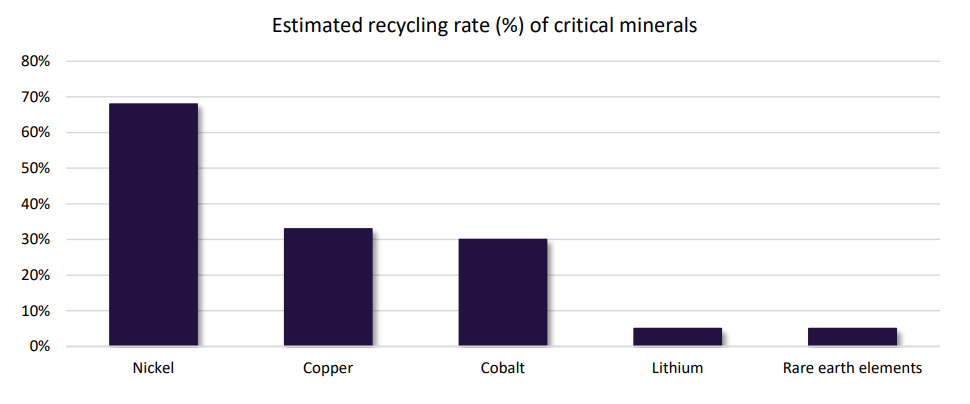

The low recycling rate of critical minerals is likely to exacerbate shortages, according to GlobalData. Source: GlobalData, International Copper Study Group, Nickel Institute, Recycling International

According to the IEA’s Critical Minerals Policy Tracker, more than 30 new policy measures on recycling have been introduced globally, and it suggests that the market value of critical minerals recycling could reach $200bn by 2050. Such growth could help to reduce the need for imports, build up mineral reserves and mitigate against future supply shocks and price volatility.

IEA executive director Fatih Birol said of the findings: “Recycling is vital to tackling the challenges around critical mineral supplies and ensuring long-term sustainability. Investment in new mines and refineries remains crucial, but there is ample opportunity for recycling to maximise the resources already at our disposal. As we move into the Age of Electricity, we have to take advantage of this treasure trove of worn batteries and electrical devices that could be revived and reused, but to do so we must develop a mature marketplace for recycling to make it attractive and easily accessible.”