Feature

Dewatered tailings: a risk reduction solution for Australia miners?

Dewatering mine tailings could significantly reduce the economic and reputational risks involved in managing tailings facilities. Heidi Vella finds out why Australia could lead the way in dewatered tailings technology.

Tailings dam and processing plant of a gold mine in the Northern Territory. Credit: Steve Lovegrove / Shutterstock

In 2019, when the Brumadinho tailings dam breached at the Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine in Brazil, wiping out an entire village and killing 270 people, the world determinedly turned its attention to mine tailings facilities.

Tailings are an unfortunate, but inevitable, part of the mining process and Brumadinho was not the first – and likely won’t be the last – incident to lay bare the devastation a tailings facility breach can cause.

One silver lining is that from the disaster emerged a stakeholder-wide resolve to dramatically reduce the risks associated with tailings management. This gave birth to the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM), convened by the UN, the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) and the Principles for Responsible Investment, which outlines best practices for tailings facilities.

Dewatered tailings as an alternative solution

Among other things, GISTM advises miners to consider alternative technologies to conventional tailings management. One of them is dewatered tailings technology.

The risk from tailings is mostly related to the amount of fluid in a facility; the more fluid, the faster and further the slurry will travel amid a breach, carried by the water. In comparison, a solid mass mobilises much less.

Dewatered tailings technology filters and extracts water from ore processing waste to produce a paste or bulk cake-like consistency. How much water can be removed depends on the type of tailings, but in a classic dewatered set-up, experts say volumes are expected to be reduced by around 30–40%. This water can then be reused in the processing facility or filtered for other uses.

Anglo Gold Ashanti’s Sunrise dam near Kalgoorlie and BHP’s Nickel West in Western Australia both dewater their tailings. Despite the technology being around 25 years old, it is not widely adopted, but miners are starting to reconsider it. BHP is believed to be evaluating multiple dewatering technologies for its Australian operations.

The drivers for investment are increasing. Under GISTM, which must be followed by ICMM members including BHP and Rio Tinto, companies need to demonstrate their final tailings facility choice isn’t based solely on cost but also on reducing overall risk, efficient use of resources, and considers benefits and impacts on communities and the environment.

Growing waster scarcity is pushing miners to consider solutions that conserve and reuse water, such as dewatered tailings technology.

This matches investor sentiment. Earlier in the year, a group of financiers managing more than $25trn said they plan to challenge mining companies that have not yet committed to a tailings dam best-practice standard and may vote against management at an upcoming annual meeting.

Furthermore, growing waster scarcity is pushing miners to consider solutions that conserve and reuse water, such as dewatered tailings technology. The issue is prevalent in Australia, the driest inhabited continent on Earth, which is no stranger to droughts.

It is this climate that makes mines in the region particularly well suited to adopting dewatered tailings technology, according to Pepe Moreno, a mine tailings expert at SRK Consulting with more than 30 years' experience in mine waste management, who specialises in tailings facilities.

“Mines in Australia are typically located in very low-rainfall areas such as the outback,” Moreno explains. “They will therefore have less water contributing to the tailings pond, which can make it cheaper to adopt dewatering technology, compared, for example, with tropical climates such as Indonesia.”

He caveats this by adding there are areas in Australia where it rains much more and so the technology might not be as advantageous in these regions.

Other benefits for the region include low seismicity, allowing for smaller walled embankments, steeper slopes and generally more relaxed designs, he adds.

How dewatered tailings work

According to Moreno, there are two typical ways of dewatering tailings: putting tailings through a thickener and recovering water to return to the process plant, or adding polymers into the tailings pipeline just before it enters the tailings storage facility. In the latter, water quickly separates and is pumped from the facility to the process plant.

The cost of adding in an extra process – rather than just piping the slurry to a pond or embankment – is one of the main prohibitors to adoption. However, emerging technological improvements could reduce this capital and ongoing cost.

Dry stack tailings are increasingly becoming the preferred method for managing mine tailings in Australia due to several environmental, economic and regulatory factors.

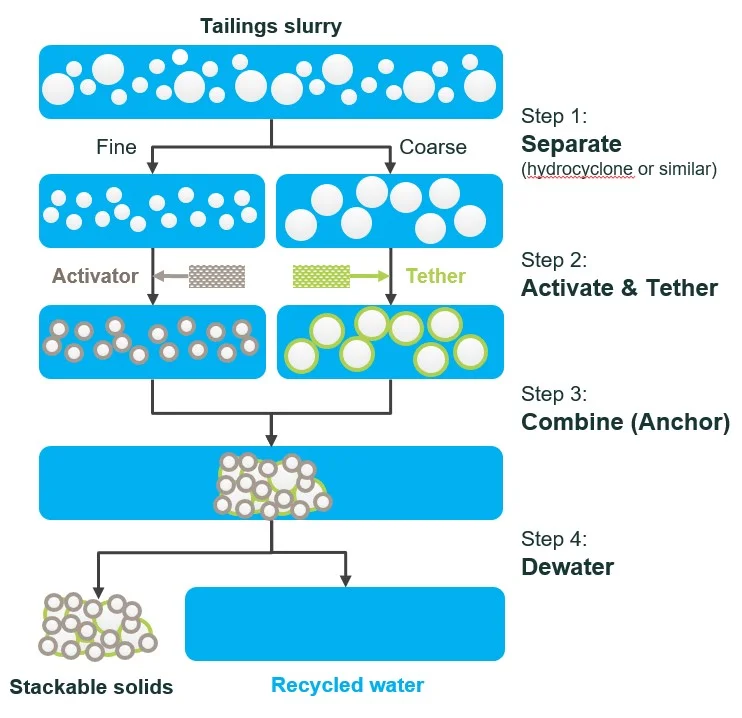

Australia-based Clean TeQ Water has developed a new dewatering technology that replaces thickeners, which it says have a high capex and maintenance cost and a large environmental footprint, with hydrocyclones and in-line mixers for a smaller and more affordable system. The technology, called ATA, is currently being trialled at BHP’s Prominent Hill operation as part of BHP’s Think and Act Differently programme.

“Making tailings that can be dry stacked requires removing a lot of water, and the main technology currently used in the market is high pressure filtration," explains Clean TeQ Water CEO Peter Voigt. "This requires large amounts of energy to compress the tailings and squeeze the water out, whereas ATA has lower capital and operating costs and smaller power requirements compared with alternative technologies."

A process diagram of Clean TeQ Water's ATA technology. Credit: Clean TeQ Water

He adds that dry stack tailings are increasingly becoming the preferred method for managing mine tailings in Australia due to several environmental, economic and regulatory factors. These include water scarcity, reducing the risk of contamination, less risk of catastrophic failure, and the fact that dry stack tailings can be easily covered and revegetated, facilitating land rehabilitation, as well as increasingly stringent Australian environmental regulations.

“From an economic perspective, recycling water lowers the costs of water sourcing and treatment, and the lower maintenance of dry stacked tailings compared with conventional tailings dams can lead to long-term cost savings," adds Voigt. "In addition, less land area is required compared with conventional tailings dams, which is particularly beneficial where land availability is limited or expensive."

In general, dewatered tailings technology is significantly improving, making it easier for bigger operations to embrace, adds Moreno. Previously, tailings volumes that could be dewatered were constrained, but this is changing with recent improvements, unlocking overall value through risk reduction.

Potential for rehabilitation and enhanced recovery

What is more, entrepreneur John Carr, who has worked for many years in mine rehabilitation, believes this development can be part of unlocking a wider value hidden in mine tailings: the potential to extract valuable resources.

Last year he set up Future Element, which aims to provide a ‘black box’ service that will dewater the tailings facilities and extract metals and minerals from the waste stream to sell.

“Dewatering tailings is only about recovery of water itself. What we are trying to do is offer something more holistic, bringing the funding, getting closer to complete rehabilitation and extracting the value to help pay for it,” he explains.

Future Element is working alongside Clean TeQ Water in the BHP trial to test the critical mineral potential of the slurry.

Clean TeQ Water is conducting ATA tailings dewatering trials with miners in Australia, South Africa and Brazil. Credit: Clean TeQ Water

Carr adds that the model can potentially help lower liability costs at mine closure. For example, his previous company, New Century Resources, purchased MMG’s Century mine in Australia, which had an accumulated 79 million tonnes of tailings. After closure and through its programme of rehabilitation and resource recovery, Carr says New Century reduced the closure cost from $387m (provision on the balance sheet) to $73m and created more than $776m in value.

The concept taps into a cultural shift in regions such as Australia and the US, where attitudes are moving towards reducing the footprint of mining operations.

“If you can develop a mine and put your tailings down a river with no consequence then there isn’t really incentive to do this,” Carr says. “Alternatively, you may not be able to develop your next mine unless you do something that really limits your disturbance. Australia is like this, there is more of a groundswell of support around doing things better, which is why we have been focused there.”

Making the right choice for tailings management

Still, Moreno cautions that dewatering tailing is not suitable for every commodity, and other challenges exist, such as managing surplus water that can’t be reused in the process facility and dealing with dust, which can be a problem in very dry areas.

To determine whether dewatered tailings are suitable for a mine site, the operator must conduct a multiple criteria analysis. This involves studies of alternatives based on different categories such as constructability, risk profile, stability and cost, assigning each a score to determine suitability. This also creates an auditable trail of how the final solution was decided upon.

Moreno also cautions that dewatering solutions are not a silver bullet. “It is not just about adopting a technology and walking away or thinking it will solve the problem. Tailings management is about proper governance, getting the right kind of design – it is hard work,” he says.

It is hard work that will likely continue to be in the spotlight under GISTM and the global shift towards better governance and accountability around mining operations, as well as better stewardship of resources.