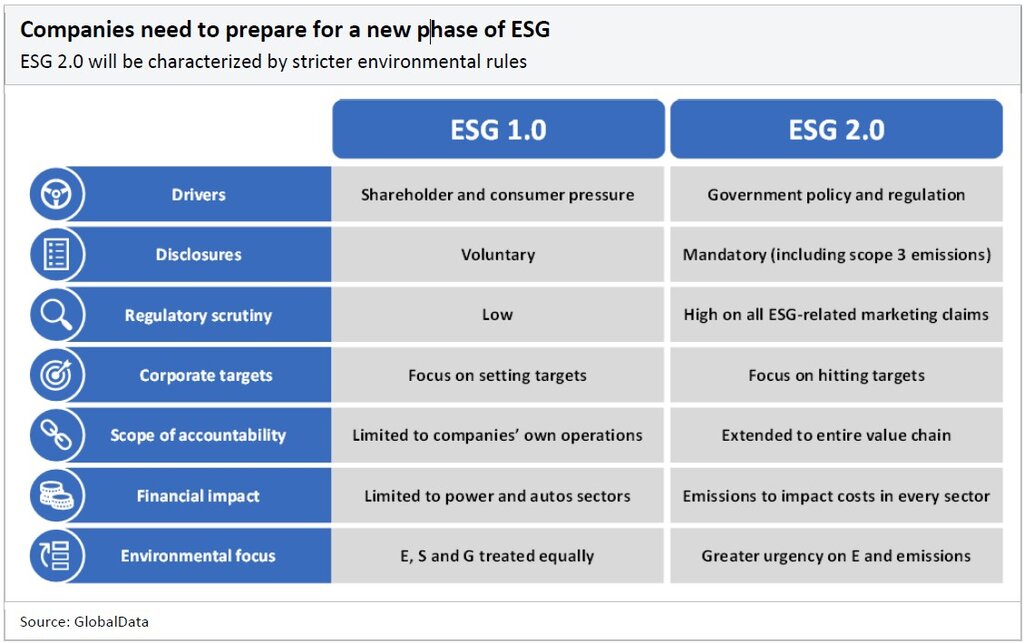

ESG, especially the ‘E’ component, is now shifting from a voluntary regime to a mandatory one, driven by government regulations rather than consumer and shareholder pressure. It is no longer enough to have an ESG strategy focused on reporting and setting targets for some distant future date. Companies need to show that they are taking action on ESG issues, especially emissions, across their value chain. The graphic below shows what companies can expect during ESG 2.0.

Drivers

While ESG 1.0 was driven by voluntary corporate action, spurred by pressure from activist consumers and investors, ESG 2.0 is being driven by a new wave of government policies.

The EU has taken the regulatory lead, with rules introduced or in the pipeline that will price emissions, regulate the use of the terms ‘ESG’ and ‘sustainability’ in marketing materials, and make ESG reporting mandatory. The US has taken a different approach, favoring less regulation and more financial support in the form of tax breaks for clean industry (renewables plus nuclear and hydrogen). China is planning to expand its emissions trading system to more sectors, decarbonize its heavy industry, and ramp up its use of renewables.

The new policy direction is mainly motivated by the ambition to hit net zero emissions targets. But on top of this, governments are now competing for clean industry and trying to challenge China’s leadership on the production of the world’s green technologies such as solar panels and batteries, as well as the production and refinement of materials needed for energy transition such as lithium. These driving forces are leading to policy that will impact every sector, not just heavy industry, and will keep ESG near the top of the regulatory agenda over the longer term.

Disclosures

ESG reporting by corporates was voluntary under ESG 1.0 but will be mandatory under ESG 2.0. Some ESG reporting rules have already come into force.

From 2024, UK companies will need to produce reports aligned with recommendations from the Task Force for Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). These reports contain metrics such as emissions as well as more qualitative governance information such as how a company assesses its climates risks and where responsibilities for these lie with the business. The 2024 reports will cover the previous reporting year, which means that UK business need to start preparing to produce such reports immediately, if not already.

Other mandatory disclosures are being finalized throughout 2023, including in the US, the EU, and at the global level through the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). Despite the efforts of global regulators to coordinate, there are likely to be different ESG reporting requirements across key jurisdictions, which will create an additional reporting burden for companies with cross-border operations. Smaller companies that fall outside the scope of these rules may also come under pressure to collect and report ESG data as larger enterprises may need to gather data from across their value chain.

Other EU laws will also require additional reporting. This includes the EU’s new carbon border tax, its deforestation law, and environmental due diligence rules, which are described in more detail below.

What is common across all new reporting standards is the requirement for Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions to be reported. Scope 1 emissions are those directly produced by a business such as a gas boiler in an office building or by burning fossil fuels for power. Scope 2 emissions are indirect and for most businesses are the emissions produced by purchased electricity.

Scope 3 will be the most challenging to calculate for most businesses. These cover emissions that a business is indirectly responsible for through its suppliers and customers, and what it includes varies from sector to sector. For example, car manufacturers include emissions produced by their cars after they have been sold.

Scope 3 emissions for the retailer Ikea, for instance, include emissions from customer car journeys to its stores. Scope 3 is challenging for businesses because it is difficult to identify what should be counted and it often requires data to be estimated or collected from the value chain.

Companies need to prepare for mandatory disclosures by developing internal ESG expertise and systems for tracking and reporting emissions and other required ESG metrics. Software that can automate elements of ESG reporting and carbon emissions tracking across supply chains is already a growing market, with large investments from technology giants such as Salesforce and IBM.

Regulatory scrutiny

While companies could use terms like ‘green’ and ‘sustainable’ fairly liberally in marketing materials under ESG 1.0, under ESG 2.0, regulators will apply greater scrutiny to ESG-related marketing claims.

In the early 2000s, BP (formerly British Petroleum) attempted to rebrand to Beyond Petroleum in an attempt to reinvent itself as a cleaner energy company. It quietly buried its new branding after two major oil spills and a lack of investment in renewables. While it may have suffered some small public relations embarrassment for its U-turn, such cases are now more likely to result in fines and other legal consequences.

For companies developing ESG strategies, ESG-related marketing and communications must come toward the end of that strategy, after the company has understood its key ESG issues and put itself on track to meeting commitments it has made, rather than at the beginning.

Regulators are coming down harder and more frequently on dubious ESG marketing claims. The current regulatory focus is on the fund management industry, with the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) in the EU and the Sustainable Disclosure Regulation (SDR) in the UK seeking to restrict the use of the terms ‘green’ and ‘sustainable’ specifically to products that comply with clear definitions. Even without such formal rules, disclosures will add transparency, making it more difficult to exaggerate sustainability performance.

One result of a robust greenwashing clampdown is likely to be greenhushing, where companies make less noise around ESG claims for fear of greenwashing accusations. More formal regulation is likely across non-financial markets that will explicitly seek to define and prevent greenwashing. In March 2023 the EU proposed a Green Claims Directive, that would require any ESG-related advertising claims to be backed by an independent verifier.

Corporate targets

Under ESG 1.0 it was enough to set targets; ESG 2.0 will need corporates to make progress toward those targets.

The vast majority of large, listed companies have set ESG-related targets. These are likely to include a target for cutting their emissions or emission intensity (their emissions per unit output or unit revenue) to zero by 2050 or earlier, with some intermediate targets in between, a common one being 2030.

It is often the case that companies will have their targets verified by the Science-Based Target Initiative (SBTi). SBTi verification assesses whether a target is consistent with emissions following a pathway consistent with the Paris Agreement target of less than 2°C. SBTi verifications do not assess the plausibility of an emissions target or the strategy the company is undertaking to achieve it.

Under ESG 2.0, companies are coming under more pressure to hit targets, rather than just make them. This pressure comes from a variety of sources including shareholders and other stakeholders that will want to see progress as 2030 nears. Pressure to hit targets will also come from the regulatory push into carbon pricing, and this will be especially true for businesses operating in, or exporting to, the EU.

The EU is broadening the scope of its emission trading system (ETS), which requires heavy polluters to purchase allowances for their emissions. It will include road transport, shipping, and buildings, and remove free allowances given to certain sectors. These changes are being phased in between 2023 and 2034. It means that companies that fall behind in reducing their emissions, especially those selling within or into the EU, will have higher costs than lower-emission competitors.

Scope of accountability

ESG 1.0 was for the most part focused on companies own operations, while ESG 2.0 will focus on the entire value chain.

The new regulatory landscape will bring a greater focus on value chain emissions. Calculating and reporting Scope 3 emissions will require companies to collect or estimate data from their value chains, and as companies try to reduce their Scope 3 emissions, more pressure will be put on suppliers and customers to reduce their emissions.

Pressure on value chains will not stop there. As part of its stricter regime of carbon pricing, the EU is bringing in a carbon border tax known as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The CBAM is designed to create a level playing field between EU businesses that must pay high carbon prices under the new ETS and foreign businesses not subject to high carbon pricing. It means companies with higher emissions will find their products face a higher tax at the EU border.

The EU is set to finalize a deforestation law over the remainder of 2023 that will likely come into force in early 2025. Under the new law, companies will only be able to sell certain products in the EU if the supplier has issued a due diligence statement confirming that the product does not come from land that was deforested after 2020.

The law covers cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, soya, and wood as well as derivatives of these such as furniture, chocolate, and leather. As part of their due diligence statement, suppliers must provide the longitude and latitude of the land where the product was sourced.

This is on top of the EU’s proposed Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive and EU Forced Labour Regulation, which would require firms to conduct due diligence on their supply chains to check for environmental harms and forced labor.

US and EU policy is increasingly trying to encourage the onshoring of production and securing supply chains of critical energy transition technology and materials as they try to reduce their reliance on China. The US Inflation Reduction Act is an example of this. It provides tax credits on electric vehicle production but only if the vehicle and its components were produced mainly in the US or in countries where the US has an FTA.

The focus on value chains will make international trade more difficult for businesses exporting and importing and variety of products. Those companies that can minimize their environmental impact and report accurate, detailed environmental-related data will have the easiest time accessing international markets.

Financial impact

While ESG 1.0 had a financial impact on the automotive and power sectors, more businesses will find that ESG performance, especially emissions, will begin to directly impact their financial performance under ESG 2.0.

The EU’s ETS and CBAM will subject a variety of sectors to higher carbon prices and import costs. Other countries are likely to adopt similar prices as having an equivalent carbon price will make it easier to export to the EU. Companies that cannot cut their emissions will find their costs climbing.

Companies that can cut their emissions intensity by more than their competitors are likely to win more clients and contracts as firms up and down value chains try to cut their Scope 3 emissions.

The flipside is a growing green opportunity for established companies, start-ups, and others looking to deliver a low-carbon economy. The US Inflation Reduction Act, which provides tax credits for green tech, is designed to grow the US’s domestic green industry and has already led to billions of dollars of announced investment in battery and electric vehicle plants. Spooked by a potential loss of industry to the US, the EU is planning its fiscal response.

The global race for green industry creates opportunities for enabling technology and innovation across multiple sectors. While many firms will see ESG 2.0 as an increase in compliance costs, firms that become sector ESG leaders will have an easier time keeping those costs down and gaining market share.

Environmental focus

Under ESG 1.0, companies needed to pay equal attention to E, S, and G factors. This will change under ESG 2.0, with priority placed on environmental factors, especially emissions.

Companies’ social impact and their corporate governance will still be important, but government policy around emissions and environmental impact is moving at a rapid pace.

Under ESG 1.0, a company that performed poorly on environmental issues might suffer some public relations embarrassment, but under ESG 2.0, poor performers will start to notice an impact on their operations and finances. Their costs are likely to be higher due to the spread of carbon pricing. It will be more difficult to trade as buyers and suppliers demand high-quality emissions data for calculating their own Scope 3 emissions.

They may miss opportunities for growth by failing to invest in low-carbon goods or services or receive fines from regulators for any marketing that describes their product or service as environmentally friendly.

GlobalData, the leading provider of industry intelligence, provided the underlying data, research, and analysis used to produce this article.

GlobalData’s Thematic Intelligence uses proprietary data, research, and analysis to provide a forward-looking perspective on the key themes that will shape the future of the world’s largest industries and the organisations within them.