Q&A

New recruits: the hiring challenges of Australian mining

Many industries have been disrupted in recent years, and Australian mining is no different. Giles Crosse speaks to Zenith Energy COO Graham Cooper about both the challenges and the opportunities this new world presents.

T

he Covid-19 pandemic, increasing uncertainty in global supply chains and ongoing industrial disruption in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine have highlighted the importance of skilled, experienced workers.

This is particularly relevant in Australia, where mining is responsible for both a significant portion of national GDP, and a source of stable employment for a sizable section of the population.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics reports that the sector was responsible for 10.4% of total GDP between 2019 and 2020, more than any other single sector, and the country’s Minerals Council noted in July 2021 that over 250,000 people were permanently employed in the industry, years into the disruption wrought by Covid-19.

Yet despite what may be the sector’s reputation as one prone to conservatism and adverse to change, the industry can be one of the fastest-moving in the world. With many mines a proving ground for new technological innovations, and a socially-conscious workforce and shareholder base frequently pushing miners to new standards of environmental, social and governance responsibility, finding highly skilled and highly flexible workers remains a constant challenge.

// Zenith Energy COO Graham Cooper. Credit: Zenith Energy

Giles Crosse: What are the key challenges facing recruitment in Australian mining and resources?

Graham Cooper: The sheer number of resource projects currently under development, and the speed at which they are progressing, has driven a severe shortage of appropriate skills in the market, which remains the major challenge in the medium-term.

Construction projects are resource-intensive and some would argue short-term personal rewards are generally [a higher priority] than projects in an operation or production phase, and yet recruiting for maintenance and production roles must come from the same limited labour pool.

Where production projects offer employees the opportunity for longer-term benefits such as ongoing training and personal development, on top of competitive salaries, the current tight labour market is pushing up remuneration offerings, which is becoming increasingly challenging to compete with in the short-term.

Regarding global supply chains and geopolitical tension, how do these impact hiring?

We’ve been dealing with issues within the global supply chain for more than two years now, resulting in an increased focus on transparency around project scheduling, particularly for those projects under construction.

While improved asset management, planning and spending in spares and stock holding for maintenance has made a difference, challenges still remain. Open communication with clients and suppliers has been vital to ensure any delivery and supply issues are identified early, and appropriate contingencies put in place throughout various planning stages, whether that be in construction or maintenance.

In recent years we’ve also looked to increase our skills in-house in areas such as fabrication and the manufacture of equipment and structures required to complete our projects, which has also assisted in easing some of the pressure.

We’re also seeing other changes, for example, where manufacturing offshore has previously been cost-driven, we’re now seeing a slow shift where the advantages of manufacturing locally in terms of scheduling, timing and security of supply outweighs the [costs]. This is good for local manufacturers, but the ongoing skills shortage and increased employment costs may also restrict this growth.

One would hope the transition to net-zero and renewables would drive recruitment and skills? Is this developing as you might wish?

It drives a different skill requirement, and what we’re seeing currently is the speed of development and sheer number of renewable installations means it is difficult to establish the required skills development processes to manage the assets long term.

In the same way that we managed energy transitions from diesel to gas and gas distribution, we are relying somewhat on original equipment manufacturers and international experience to kickstart our local knowledge and skills.

Definitely the industry is continuing to build experience and skills in ‘traditional’ renewables such as solar and wind, while at the same time the progression of alternative fuels such as hydrogen and green-diesel will also speed up development and assist companies in reaching various targets.

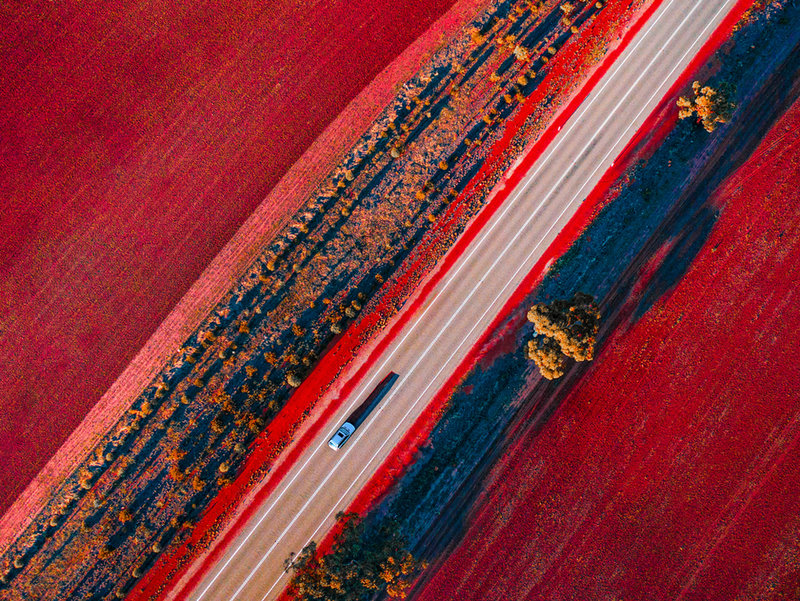

// Main image: 3D System Model and Completed Installation. Credit: Deimos

Right now the world faces a climate crisis, and to an extent an economic one too. How can hiring the right people help balance the need for power and environmental and economic responsibility?

Recruiting and retaining the right people is critical to any business success, and in terms of transitioning toward net-zero, it’s important to have people onboard that also share your vision and goals.

From a remote power perspective, that also means securing the support of those who are transitioning away from high-emission, inefficient power systems to the current efficient, greener power systems. It’s also important that the essential requirement of reliability is not discarded or overlooked as part of the transition to sustainable power generation.

From the current levels of education, investment and research into renewable power systems in the industry it’s clear there is a desire to experiment in this area, but we must also maintain reliability during the transition to ensure the confidence of the resources industry to incorporate or invest in emerging ideas is not dampened.

Do legacy industry approaches to both people and extractives in general in Australia need a rethink? And what might the future hold?

I think it’s important for industry to periodically look at its approach and look for ways to do things better or differently, using the knowledge and skills gained over time. It would take a major shift in thinking, but can we get to a point where mining operations are able to remain profitable by operating only at times when sustainable power generation is available?

Fossil fuel pricing, distributed mining centres, battery energy storage and intercontinental energy sharing would all have parts to play in such a shift.

What one thing must the Australian mining and extractives sector get right to manage people, and the clean energy transition?

Don’t be afraid to embrace scale and collaboration to maintain required reliability. Power generation efficiency increases with scale, and renewable energy is no exception.

Also, reducing emissions from power generation is not the only method to create greener production efficiencies. Other areas can also be looked at, such as water use, and the effective management and recycling of waste.

Renewable energy [and] electrification are currently the key areas of focus in terms of reducing emissions, and this has come off the back of serious investment and leveraging success elsewhere in the world. However, organisations should also be encouraged to explore, experiment, and innovate to develop other sustainability opportunities, and not be bracketed to power as the entire solution.

What might you consider an ideal Australian mining sector in 20 years time, as net-zero targets approach?

A sector where there is opportunity for employees, investors and innovators, where critical sustainable assets such as power and water are available to the comparative benefit of all.

Mining remains one of the sectors in Australian business where there is a vast array of players, from single-mine, small scale operations, right through to multi-mine multinationals. Transitioning to sustainable practices and particularly renewable energy supply requires significant initial investment, and some smaller operations may not be able to participate as effectively.

Regulators and those looking to place particular targets on industry need to consider this carefully. For me, an ideal mining industry is one that can continue to provide the career opportunities and job security that it does currently, while also operating sustainably for the benefit of the whole community.

// Main image: Two engineers. Credit: SeventyFour via Shutterstock