MONITORING

How satellite images of illegal mining can force action on the ground

Projects that monitor the extent of illegal mining and deforestation in the Amazon are now able to provide near-real time satellite images showing the scale of damage. Matthew Hall explores how these projects are able to instigate action on the ground and looks at the barriers that NGOs and researchers face in turning often shocking images into actual change.

S

even years ago, the United Nations Climate Summit endorsed the New York Declaration on Forests (NYDF) – a pledge to halve global deforestation by 2020 and end it entirely a decade later. Within five years of the UN endorsement, the list of national and sub-national governments, multinational companies, NGOs, and indigenous groups supporting the declaration had grown to over 200.

2020 came and went, and rather than halving since 2014, the rate of deforestation has increased. Ending global deforestation by 2030 looks impossible by current practices, and the NYDF’s own progress assessment says that hitting that goal will “require a paradigm shift” in how we value our forests.

The assessment identified the resource sectors as a rising risk to forests, with the pace of infrastructure development and resource extraction increasing across many tropical forest regions. Growing demand for mined commodities and fossil fuels is also putting pressure on these ecosystems.

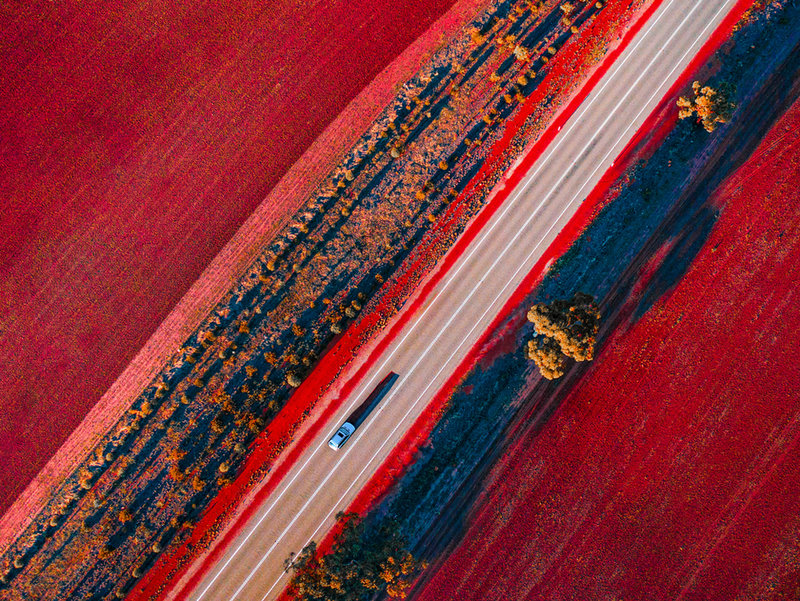

A bird’s eye view

The proliferation of high-resolution satellite imagery has meant that the effects of deforestation can be viewed from above, with projects like The Amazon Conservation Association’s Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) using near real-time imagery to flag potential areas where illegal mining or other activities is causing deforestation.

Mapping deforestation hotspots begins with data from Landsat, the joint program between the US Geological Survey and NASA.

This data can show areas of possible concern, and from there the MAAP team can focus on a particular area using near real-time satellite imagery where changes on the ground can be seen day to day. A high-resolution satellite image can then be taken of the area and shared with local and national governments.

When we launched in 2015, illegal gold mining was literally tearing apart the southern Peruvian Amazon.

MAAP regularly releases images online chronicling the extent of ecological damage in the Amazon, as well as providing reports directly to governments.

“When we launched in 2015, illegal gold mining was literally tearing apart the southern Peruvian Amazon, just hundreds and then thousands of hectares of a primary forest that was just getting eaten away,” MAAP Director Matt Finer told Mining Technology recently.

MAAP’s work in the Peruvian Amazon has yielded positive results with documented improvement on the ground through Operation Mercury – the Peruvian Government’s crackdown on illegal gold mining in the southern Peruvian Amazon.

Operation Mercury was initially focussed on an area known as La Pampa, an epicentre of illegal mining. Subsequent analysis by MAAP revealed a 90% decrease in illegal gold mining deforestation in La Pampa resulting from Peru’s intervention.

Falling on deaf ears

While Operation Mercury resulted in a successful (and continuing) crackdown on illegal mining in the Peruvian Amazon, the efficacy of overhead images of deforestation can be limited by what governments and other authorities on the ground are willing to do with them.

This can be a particular issue for Amazonian countries – an ecosystem of international importance is beholden to the policies of national and local politicians. This becomes a problem when one of these nations – let’s say Brazil – is led by a president that wants to exploit the resources of the rainforest, and whose rolling back of environmental policies has spurred calls for the International Criminal Court to investigate said president.

An ecosystem of international importance is beholden to the policies of national and local politicians.

MAAP is aware of these issues and has strategies to pursue when a government is not immediately willing to curb deforestation within its borders. Brazil is home to more than half of the Amazon rainforest, and global concern for the lungs of the Earth means that there is already considerable pressure on Brazilian politicians from the international community.

“MAAP specialises in real time monitoring and we developed a unique system to communicate with government when we detect illegal gold mining,” Finer explains. “First, we send a confidential report and give authorities time to respond, but then eventually go public with the information for added pressure.”

Finer says this strategy has yielded effective results in Peru.

The power of social media

Indeed, the internet plays a role in ensuring satellite images of deforestation reach a wider audience – and social media itself can create pressure to act. SOSOrinoco is an advocacy group founded in 2018 working to highlight deforestation and illegal mining in the Amazonas and Orinoco regions of Venezuela.

The Orinoco river basin covers over 340,000 square miles, and the small team relies heavily on satellite imagery to demonstrate the extent of illegal mining and identify deforested areas.

Political will to deal with deforestation has been close to non-existent. In 2016, President Maduro opened the Orinoco Mining Belt, encouraging investment from Venezuelan and foreign mining companies. Maduro implemented the idea, which was initially envisioned under his predecessor Hugo Chávez, to offset the decline of oil revenue in the country.

Political will to deal with deforestation has been close to non-existent.

SOSOrinoco uses social media platforms to raise awareness of the environmental issues facing the Amazonas and Orinoco regions, distilling its analyses into short video clips that have amassed tens of thousands of views on platforms such as Twitter.

In 2019, the group even participated in the #10YearChallenge, an end-of-decade social media trend where users posted photos of themselves taken ten years apart – co-opting the viral hashtag to raise awareness of deforestation in Venezuela.

SOSOrinoco said the impact of these viral videos goes further – in addition to educating the general public the videos catch the eyes of journalists, politicians, and activists, spurring greater interest and creating more pressure on Venezuelan officials to curb deforestation than might otherwise have been possible.

// 3D System Model and Completed Installation. Credit: Deimos