COP26

The spectre of scope three: indirect emissions and net-zero ambitions

While most of the world’s diversified miners have established a reduction plan centred around their scope 1 and 2 emission profiles Zachary Skidmore asks why, the majority have yet to set scope 3 targets, which make up much of mining’s overall emissions.

W

ithin the mining industry, there are three scopes of emissions: scope 1 covers direct emissions from operations, scope 2 covers indirect emissions from power generation, and scope 3 covers all other indirect emissions. Within mining, scope 1 and 2 emissions account for 4%-7% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This rises to 28% of global emissions however when accounting for scope 3, according to January estimates from McKinsey & Co.

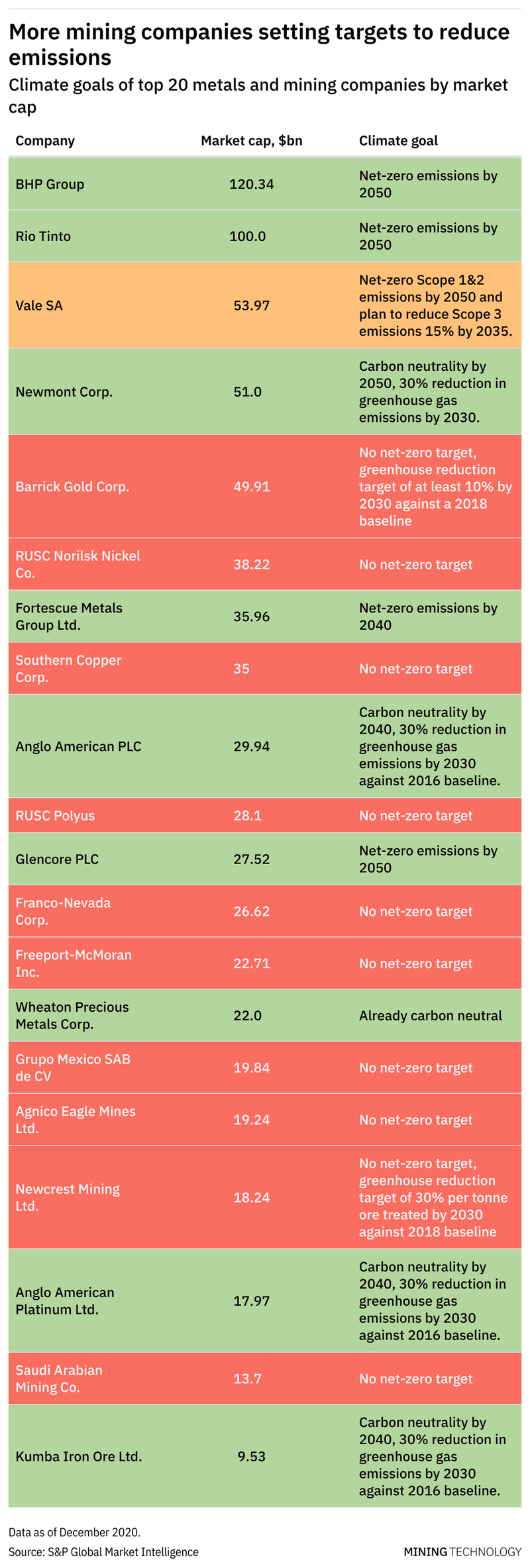

Most diversified miners have focused on the reduction of their scope 1 and 2 emissions through various methods. Miners including Glencore, Newmont, BHP, Vale, and Rio Tinto have all committed to carbon neutrality by 2050. However, some laggards, such as Rustic Norilsk Nickel, Southern Copper Corp, and Freeport-McMoran, lack any net-zero target.

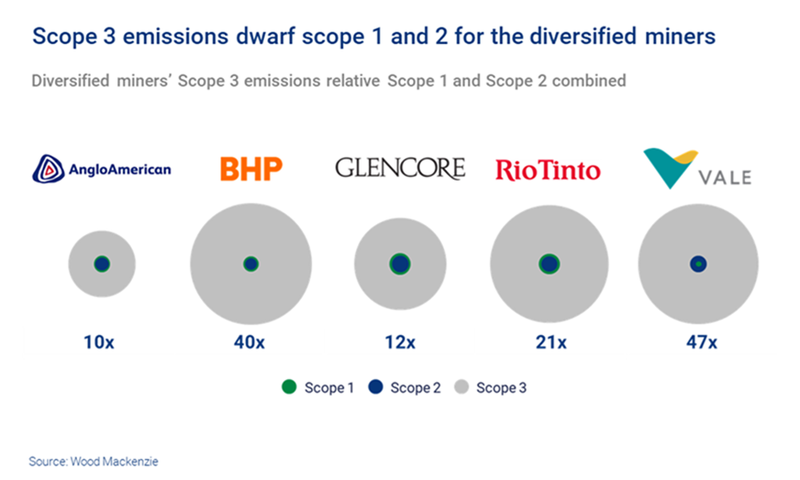

Where the major diversified miners most differentiate is in their actions towards scope 3 emissions. Scope three usually accounts for the highest proportion of their carbon footprints, with estimates as high as 95% of total mining emissions. The average of the five largest diversified miners (figure 2) is 26 times their scope 1 and 2 emissions combined.

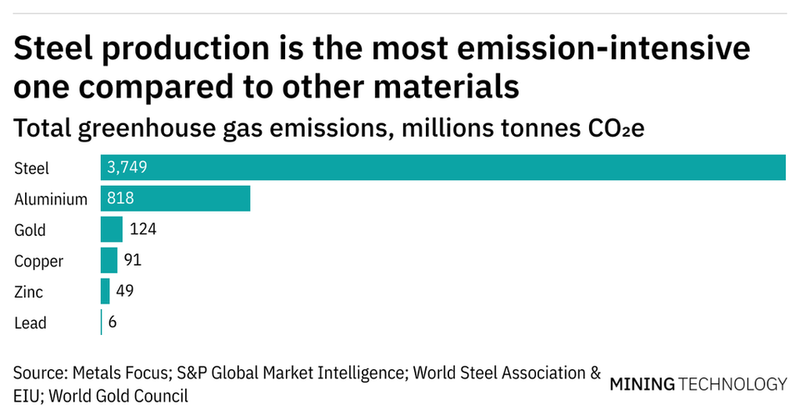

Despite the difficulties, Glencore and Vale have set precise scope three goals. But they are very much in the minority of miners, especially those invested in iron and steel production. Steel is the most emission-intensive material, accounting for 3,749 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MTCO2e) in 2020, compared to 818MTCO2e for aluminium, the second-highest polluter.

For large iron ore producers such as Rio Tinto and BHP, this creates an issue, as the majority of their scope 3 emissions are caused by steel mills in China and East Asia that use metallurgical coal. Their inability to influence these affairs has led these companies to make vague commitments towards focusing on technological advancements and energy efficiency, rather than setting specific target reductions for scope 3 emissions.

Leaders in scope 3 reduction

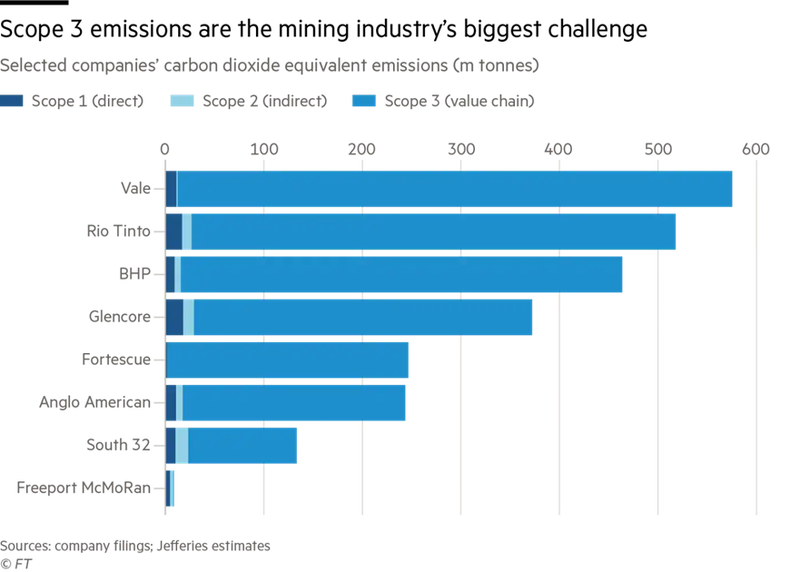

Vale is one of the companies that has recognised the importance of reducing its scope 3 emissions. In 2020, Vale’s activities resulted in 491.1MTCO2e, more than 97% of which was attributed to indirect scope 3 emissions. Vale’s CEO has stated in response that, after “an initial estimate, Vale will be able to account for up to 25% of the total scope 3 reduction target through its portfolio, which sets the company apart from global competitors”.

Referencing 2018 as its baseline year, Vale registered 586MTCO2e from their value chain. The company plans to reach 496MTCO2e in 2035, down 90MTCO2e from 2018, equal to Chile’s emissions from energy consumption in the same year. Vale will review the target in 2025 and every five years after that.

The company has committed to a range of actions. Since 2014, Vale has supplied some of the best mixes of high-quality products in the iron ore market, which demand less energy in the steel blast furnace and reduce emissions. In shipping, Vale is committed to the International Maritime Organization’s goal of reducing emissions by 40% by 2030 and absolute emissions by 50% by 2050.

Vale is committed to the International Maritime Organization’s goal of reducing emissions by 40% by 2030 and absolute emissions by 50% by 2050.

Nature-based solutions also play an essential role in this process; today, Vale helps protect more than one million hectares of forestry worldwide and by 2030, it plans to cover another 500,000 through recovery and protection projects.

Glencore is another example of a miner taking the initiative on scope 3. The organisation has projected a 30% reduction in total Scope 3 emissions by 2035. They intend to achieve this by lowering operating emissions; reducing coal production; increasing investment in low-carbon metals such as copper, cobalt, nickel and zinc; and supporting the deployment of low emission technologies.

With its high exposure to copper, nickel, zinc and cobalt, and waning exposure to coal, Glencore will become an attractive partner for a company seeking a big portfolio of “clean” metals, demonstrating its forward-thinking approach towards emission reduction.

The problem with Scope 3

Scope 3 emissions have outsized importance to overall emission reduction. But as they fall out of the company’s direct control, many companies avoid making direct statements on their reduction.

One of the major factors in this avoidance is the carbon intensity of the iron ore industry. Anglo-American, BHP, and Rio Tinto are all big producers of iron ore, with Rio Tinto alone producing 285.9 million metric tons of iron ore in 2020.

The main problem for these miners is that the heavy industries that turn iron ore into iron and steel are largely located overseas, in Chinese state-owned steel mills.

The steel sector is one of the biggest polluters in China, producing around 10%-20% of carbon emissions in the country, with production only ramping up. In the first half of 2021, Chinese steel mills churned out nearly 12% more crude steel compared to the same period in 2020.

In H1 2021, Chinese steel mills churned out nearly 12% more crude steel compared to the same period in 2020.

This lack of control has resulted in spiralling scope 3 emissions for several major miners. But miners can do more, according to Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation research scientist Keith Vining. He stated: “One of the biggest emitters of carbon in the iron making value chain is the use of metallurgical coke in the blast furnace, and the simplest way we can influence how that is reduced is by upgrading the material before shipping it overseas”.

Japan is actively researching carbon intensity reduction in its iron and steel industry by introducing hydrogen into the blast furnace. This would significantly reduce the reliance on metallurgical coke. Despite the significant challenges, according to Vining, this “raises the possibility of the iron and steel value chain going that step further to produce ‘green steel’”.

Impact of the iron ore industry

Major miners have committed to focus on the investment into technology to reduce the carbon intensity of steelmaking. Rio Tinto, whose scope 3 emissions measured at 491MTCO2E in 2020, set a target of at least a 30% reduction from 2030 in conjunction with the development of breakthrough technology with the potential to deliver carbon-neutral steelmaking processes by 2050.

However, Julian Kettle, vice-chairman of metals and mining at consultancy Wood Mackenzie, said that Rio’s new emission reduction targets were a step in the right direction, but more was needed.

“A $1bn green investment, while laudable, could be funded by a $0.3 a tonne rise in the iron ore price. The industry needs to do much more,” he said.

A $1bn green investment, while laudable, could be funded by a $0.3 a tonne rise in the iron ore price.

This indicates that despite the investment until a viable low carbon technology such as hydrogen-powered blast furnaces are fully mature, the use of metallurgical coke in blast furnaces will remain the norm. Despite the ever-improving efficiency of blast furnaces, it is still a carbon-based method that makes achieving total net zero an impossibility if use continues to be high.

BHP has also signalled goals to lower its indirect carbon footprint by requiring other participants in its value chain to achieve net zero. The Melbourne-based miner’s scope 3 emissions were 402.5MTCO2E in the 12 months to 30 June, with iron ore making up an estimated 205.6 to 322.6 million tonnes contribution to that total.

However, BHP’s new goals have drawn immediate criticism from some shareholder campaigners because they fail to include the Asian steel mills that burn its coals and iron ore, which make up the biggest share of its scope 3 emissions.

Investor pressure

This comes as global resource companies are put under further pressure by investors to be more accountable for emissions beyond their operations. Influential investors, including Norway’s $1.3tn sovereign wealth fund, have threatened to drop firms that don’t meet their environmental standards.

Mark Van Baal, founder of Dutch activist shareholder group Follow This, has argued that these companies must be pressured by investors to adopt these green business models earlier to take advantage of shifts in consumer behaviour, such as increased demand for low-emissions products and services that could see the world’s largest companies realise over $2.1tn in value.

Companies must be pressured by investors to adopt these green business models earlier to take advantage of shifts in consumer behaviour.

Some miners have made an argument, such as Fortescue Metals Group, which recently announced intentions to reduce scope 3 emissions, that they resisted until they had a concrete plan that could help its customers decarbonise.

However, miners cannot wait too long to set firm commitments. Findings by the Responsible Mining Initiative, which analysed 38 of the world’s biggest listed mining firms, found that most were highlighting or overstating their positive SDG contributions in their annual reporting. This has led to significant scepticism being levied on these lofty claims of breakthrough tech and efficacy improvements that belie any concrete commitment.

// Main image: A man is watering the coal heap with pipe - Karachi Pakistan - Jun 2021.

Credit: Tea Talk / Shutterstock.com