Opinion

China’s dominance of the rare earths supply chain is a geopolitical risk

Jason Mitchell argues the Western world must draw up its own strategic plan for rare earths; otherwise, China will be able to control the price of the metals simply by adjusting supply.

T

he Ukraine crisis has shown just how dangerous it is for Western economies to become dependent on an autocracy for a mineral resource. In this case, it has been Russia and natural gas. However, there is another dependence that sooner or later the Western world must wean itself off – China and rare earth element (REEs).

REEs are absolutely essential to the “green energy revolution” underway in the West. They are also vital for the tech transformation that is happening. The 17 elements are found in myriad applications that are frequently used. For example, the bright colours of a smartphone display are produced by small amounts of yttrium, terbium and dysprosium.

Yttrium, europium and terbium phosphors are the red-green-blue phosphors used in many light bulbs, panels and televisions. Lanthanum makes up as much as 50% of digital camera lenses, including smartphone cameras.

Neodymium-iron-boron magnets are the strongest magnets known to man and are used in computer hard disks and CD–ROM and DVD disk drives. They are also used in a number of conventional automotive subsystems, including power steering, electric windows, power seats and audio speakers.

Imbalanced supply

The most important emerging markets for the permanent magnets made from neodymium and praseodymium (NdPr) alloys are generators for wind turbines and traction motors for electric vehicles (EVs). Each EV uses an additional 0.5kg–1kg of NdPr oxide compared with a standard internal combustion engine vehicle.

Each megawatt generated from a direct drive wind turbine uses 200kg of the oxide. It is estimated the number of EVs on the world’s roads could skyrocket from 11 million today to 230 million by 2030. The number of offshore wind turbines could jump to 30,000 by 2030 from 2,500 at the end of 2020.

In other words, a great deal of rare earths oxide is required for the green energy and tech revolutions to happen. Its demand is expected to jump at least fivefold by the year 2030. However, there is a huge problem – China completely dominates the rare earths supply chain. In 2021, the country made up 54% of global REE mine supply and 85% of the global supply of refined REEs. For example, about 16,000 tonnes of REE permanent magnets are exported from China to Europe each year, representing 98% of the EU market.

China has a rare earths strategic vision

China has had a strategic vision for REEs for three decades – something the West has totally lacked – and it is creating a new state-owned enterprise, China Rare Earth Group, which will control 60%–70% of the country's rare earths production. In other words, 30%–40% of global supply. The country's control of the rare earths supply chain is similar to the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries' influence over the oil market.

China can control the price of REEs by adjusting supply. It could even shut down the entire supply chain – something that would be catastrophic for the renewable energy industry, the EV industry and the smartphone and television manufacturing industries.

In the same way as Germany and Italy have realised that their dependence on Russia for natural gas creates a huge geopolitical risk, Western economies must recognise that their reliance on China for rare earths is also highly problematic. Many people believe EVs and wind turbines are critical to stop climate change, but they must understand that there is a cost; the West's growing dependence on an autocracy for the materials that support the green energy revolution.

Many people believe EVs and wind turbines are critical to stop climate change, but they must understand that there is a cost.

Let's not forget that rare earths mining can also cause terrible environmental damage. The Bayan Obo deposit in Inner Mongolia, northern China – containing 40 million tonnes of rare earths reserves – is the world’s biggest deposit but has generated a vast toxic lake close to Baotou, a city of 2.6 million people.

Consumers of smartphones, EVs and wind power in the West must be told more about the issues around the rare earths upstream supply chain. Western economies must come together and draw up their own strategic plan to end China's stranglehold over the industry. Otherwise, one day they could regret having not done so sooner.

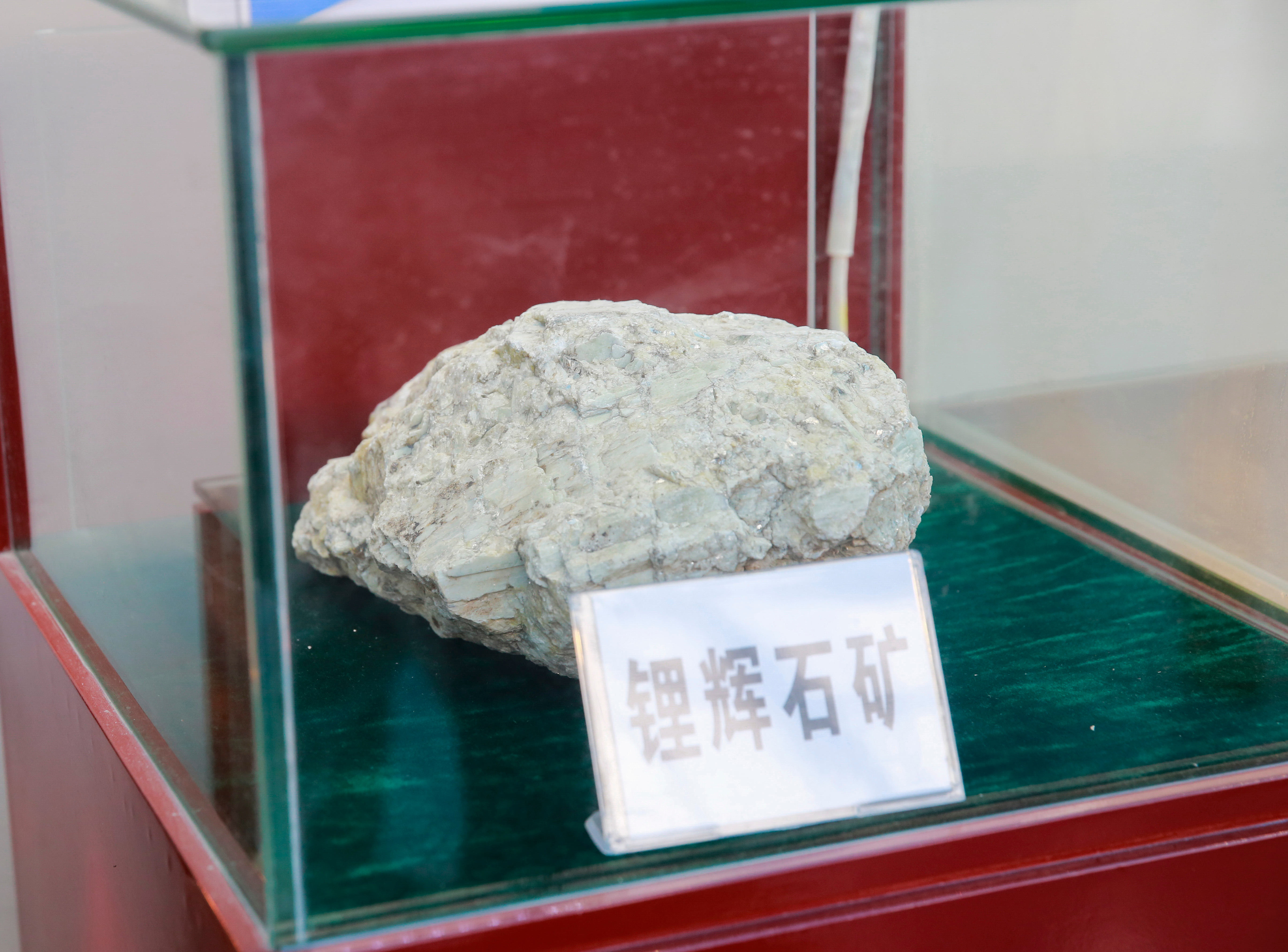

// Main image: Ore products on display in China. Credit: humphery / Shutterstock.com