MONITORING

A view from above: could satellite imagery help in the fight against illegal gold mining?

Illegal gold mining in the Amazon is a well-known practice, but a recent image shared by NASA shows the vast destruction of rainforest in the Peruvian Amazon and the highlighted impacts of unregulated mining. Yoana Cholteeva explores the work of the Monitoring of the Amazon Project and its meticulous mapping of illegal mining in the Amazon to see if this could be the time for satellite imagery to make a difference.

W

ith social media enabling images to be shared far and wide, the innovative, satellite-based, near real-time deforestation monitoring system known as the Monitoring of the Amazon Project (MAAP) has demonstrated how powerful imagery could play a key role in protecting the world’s most vulnerable environments.

For example, areas such as the lawless Peruvian district La Pampa have been taken over by independent miners, called garimperos. These miners have long been digging into the Peruvian Amazon as part of a gold rush that has only been encouraged by the metal’s price growth over the past six to seven years.

As a result of MAAP’s satellite imagery circulating in the media, in 2019, the Peruvian Government finally declared martial law in the region, dispersing thousands of miners that have been cutting down the forests to search for the precious metal.

Since then, scientists and conservation biologists have been working in Peru to investigate which tree species can survive the damage and how to support their growth.

Inside MAAP and its work towards exposing illegal mining

The MAAP project was created by Matt Finer in 2015 as a programme within the Amazon Conservation organisation to expose illegal gold mining practises that were resulting in arguably the most emblematic deforestation issue in the Peruvian Amazon.

For six years, MAAP has been using Amazon satellite images, with the twist of doing it in real time and, as Finer puts it, “that means working on the scale of days and hours, instead of years”. This work has made it possible for experts to use the imagery to compare and contrast the change of developments that have been taking place in those areas.

“When we launched in 2015, illegal gold mining was literally tearing apart the southern Peruvian Amazon, just hundreds and then thousands of hectares of a primary forest that was just getting eaten away. I make the analogy to a giant monster caterpillar because of the way that gold mining expands, slowly moving like this giant mining caterpillar,” Finer says.

When we launched in 2015, illegal gold mining was literally tearing apart the southern Peruvian Amazon.

Between 2017 and 2018, MAAP was still working to attract the attention of authorities and sound the alarm about the deforestation crisis in one of the areas, La Pampa, to lead a change. However, it took some time before the Peruvian Government responded with unprecedented action, confronting the illegal gold mining in a move called Operation Mercury.

After Operation Mercury, the role of the project shifted, with the MAAP team moving on to evaluate the impact of Operation Mercury and looking across the wider landscape of southern Peru, monitoring the spreading of miners to a different spot near the same territory.

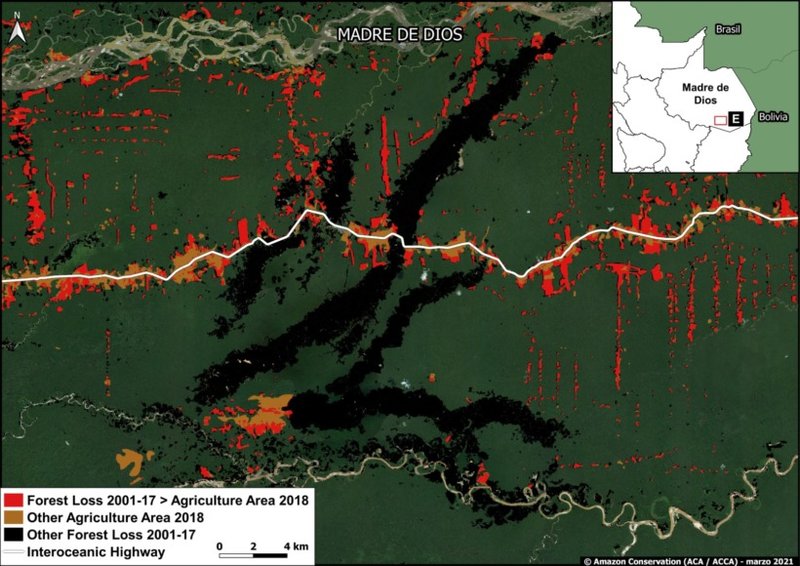

// Mining and agriculture deforestation in southern Peru (Madre de Dios region). Credit: MAAP, MIDAGRI, MINAM/Geobosques.

The success of Operation Mercury and ongoing government collaboration

MAAP’s findings have now concluded that Operation Mercury was largely successful, with gold mining reduction in La Pampa reaching 92% to date.

But it is the invaluable recognition and response from the Peruvian Government that managed to register MAAP’s efforts and turned the ideas into reality. Since then, MAAP has continued its work and collaborates with the government to report new illegal gold mining deforestation, thus putting it in officials’ hands to intervene in the unregulated activities.

I think we're cycling towards trying to get to zero illegal gold mining and deforestation.

Finer says: “So in between all our public reports, we do these confidential reports to the Peruvian Government, they call them policy briefs. We're in this really interesting cycle with these zones, we're monitoring in real time. When we notice new illegal gold mine deforestation, we inform the government.”

Following its initial success, the team has been working on follow up operations to try and eliminate illegal gold mining deforestation in new breakout zones, with MAAP having to go through the cycle three or four times.

“We noticed the gold miners had moved, we wrote a report, the government then intervened in the mining activity; but then we noticed there's another pocket, we informed the government, they would crack down on this... I think we're cycling towards trying to get to zero illegal gold mining and deforestation, which is amazing, given where we were in 2018,” he admits.

The role of the media

Speaking about the importance of the press towards the recognition of MAAP’s work, Finer says that a good collaboration between the team and the Peruvian newspaper El Comercio has had a profound impact as the publication would typically publish MAAP’s satellite images on their front page every time a new report comes out.

“It was a big deal because of how commercial the newspaper is; it sits in the offices of every ministry in Peru, so I think that helps,” he says.

We have the technology to monitor this gold mine expansion but we don't have that link to the policy impact.

Other areas with graphicly evident deforestation caused by illegal mining activities include some indigenous territories in the Brazilian Amazon. However, unlike their collaborative efforts with Peru, Finer admits that the political situation in Brazil is much different, in terms of having a national government that's promoting mining activities rather than scrutinising them.

“So, for example, in the Brazilian Amazon it is more of a challenge, we have the technology to monitor this gold mine expansion but we don't have that link to the policy impact. We have the technology to see it, but we don't have the government partners to act on it. So, ultimately, your job is highly dependent on the way governments act as well, because you can’t do all the work yourself,” he explains.

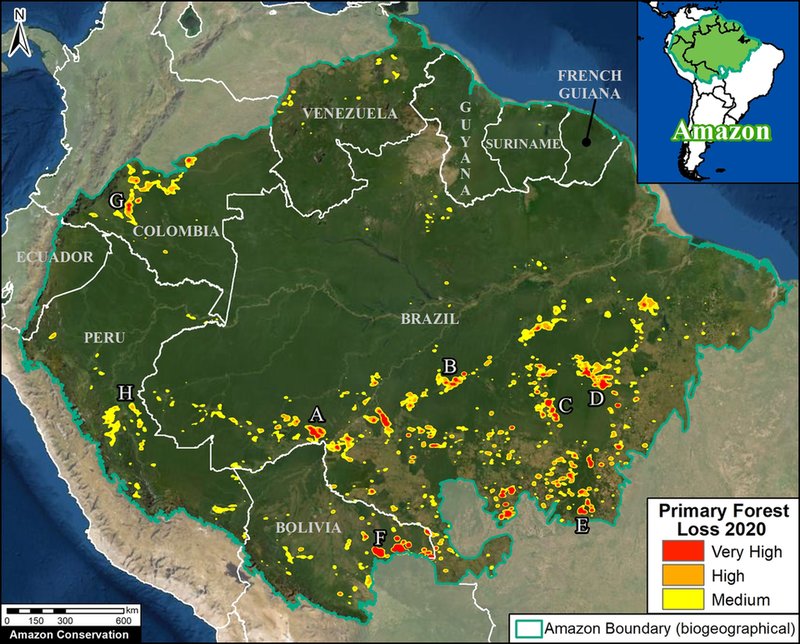

// Forest loss hotspots across the Amazon in 2020. Credit: UMD/GLAD, RAISG, MAAP.

Looking ahead to prevent land and environmental destruction

As MAAP’s duties entirely constitute the technical part of monitoring problematic sites, they say that working directly with governments is what has proven most successful.

Finer says: “We do these policy briefs, but if this doesn't work then we find another strategy. For example, in Brazil we tend to go public and work more on the international pressure, because there's a great deal of pressure on Brazil internationally to act on these issues.”

He shares that the team has noticed the shift of the Brazilian Government towards realising the need to take such matters more seriously and MAAP seems to always have another trick up its sleeve if its current one doesn’t work.

There's a great deal of pressure on Brazil internationally to act on these issues.

“Then, we reach out and work to publish this information, so civil society has it. Brazil also has a very active civil society, very active journalists, so that's our primary audience now for this dimension,” he says.

Finer shares that one of his 2021 new year's resolutions is to be more active on Twitter, to help raise awareness of the projects they work on and spread information all around the world: “I'm seeing the power of Twitter now. Instead of having to wait for us to publish a public report, which takes a lot of time and effort, I can take a snapshot of the analysis we're doing, and just put it on Twitter.

“The impact of reaching out to a handful of Brazilian journalists that are very engaged in these issues and to really utilise the power of Twitter can amplify this real time monitoring that turns into imagery, which is very striking.”

// Main image: Brasil2/iStock/Getty Images Plus. Credit: Getty Images