Staff & Culture

Susan Lomas has worked in the mining industry for over 30 years and has experienced sexual harassment first-hand. This year she founded the Me Too Mining Association to start a conversation about gender-based violence and discrimination in the mining industry. Heidi Vella speaks to Lomas to find out more

#MeTooMining:

Sexual Misconduct in the Industry

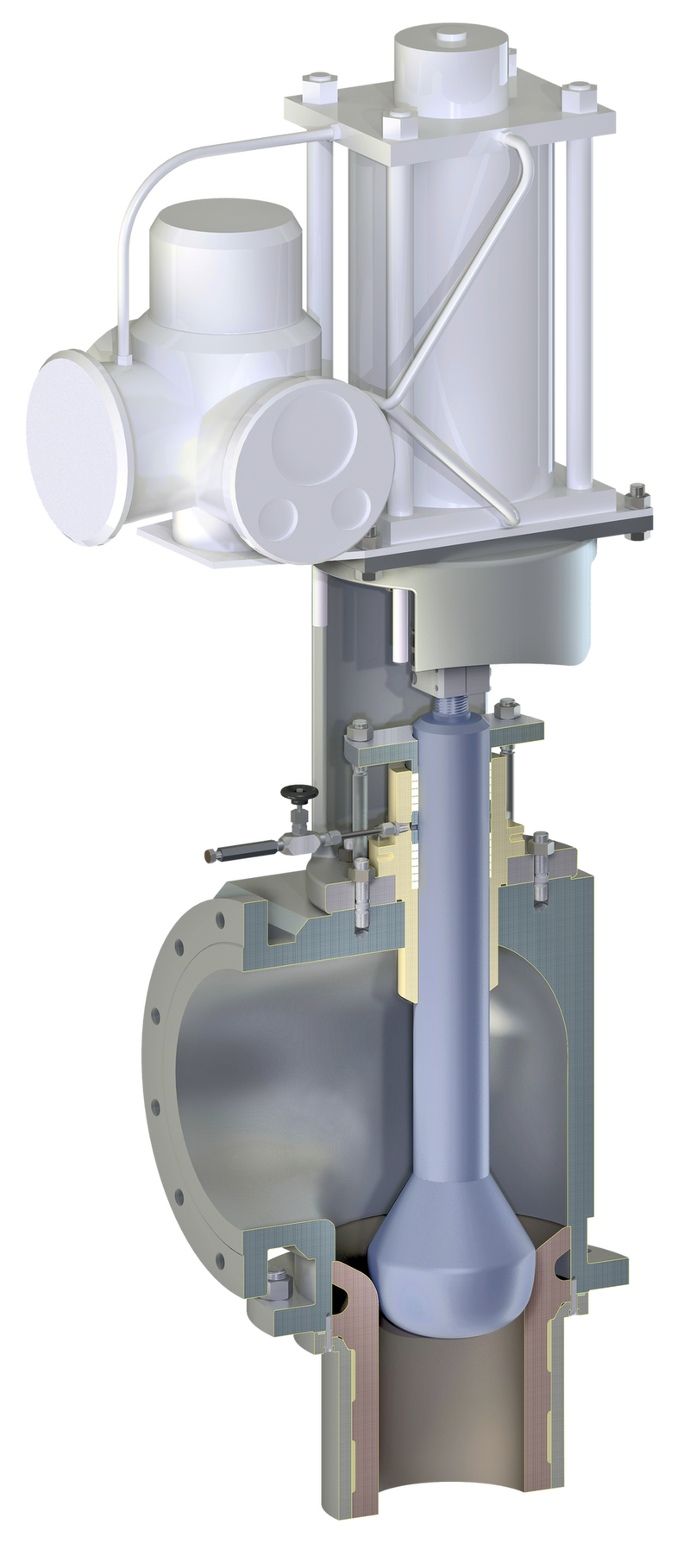

Type 74CS Angle Control Valve

Actuator Choice

SchuF can provide a full range of actuator types- manual, pneumatic, electrical, hydraulic, or gas-over-oil

Cast Yoke

These guarantee a robust and reliable actuator-to-body connection

Full range of seal-to-atmosphere options

All possible packing-ring materials can be provided, as well as further options such as live-Ioaded packing and leak-detection systems

Stem Lubrication

Available on request

Cast Body

Material selection entirely to customer requirements. The sweeping-angle body geometry provides constant media flow acceleration to the seat

Control Disc with Spindle

Providing maximum control performance and exceptional corrosion and erosion resistance utilising ceramic trim

Blast Tube

This will provide seating for the disc along with optimal flow control. Material such as Hexoloy will outperform ceramic and metal superalloys for strength, hardness and corrosion resistance

Seating Sleeve

Designed to perfectly mate with the customer’s mounting/installation point, leaving no dead-space

Scroll down to read the article

‘We come in peace, but we mean business’ is the strapline for the Me Too Mining Association website launched in January. Earlier the same month, singer and actress Janelle Monáe Robinson spoke the same words at the Grammy Awards in support of the #MeToo movement that emerged from Hollywood as a mark of solidarity with the alleged victims of sexual predator Harvey Weinstein.

From the glamour of awards season in Los Angles, to the around 80% male-dominated mine sites scattered across the world, the two settings might be polar opposites, but the stories are familiar and the message is the same: end sexual harassment in our industry. Now.

“I have seen it, experienced it and heard many more horrible and serious stories than what has ever happened to me,” says Canadian geologist, Susan Lomas. Lomas started working as a geologist at Canadian mine sites straight out of university. It didn’t take long before she experienced abuse for the first time. Her male colleagues plastered her work area with pornographic pictures, which she removed, twice. In response, the site sampler threatened to put her hand through a rock crusher.

“When I first started in the industry in the late 80s, there was this attitude of ‘you are in my space’,” she says, “I just had to try and find a place I could operate within it and keep moving forward.” Lomas tells another story of a CEO at a mining company who used to lift up woman’s shirts to see what bras they were wearing. He was never held accountable and one by one women eventually left the office.

“Working in remote sites it [sexual harassment] is almost more expected, but in the office, there is often this perception that it is going to be less intrusive, but sometimes CEOs of mining companies are very aggressive men,” she explains. “The industry has that cult of personality, they have all these people fawning all over them and this can breed a culture of impunity.”

Women on the record

There have been very few studies done to quantify the scale of abuse women face in the mining industry. However, along with Lomas, other women’s stories are being put on record, including some that are utterly horrific.

Last year, Kari Lentowicz spoke to local media about the sexist comments, gender bias and insular “boys’ club” she experienced as an employee at Cameco Corp’s flagship uranium mine site, Cigar Lake, in northern Saskatchewan, Canada. The culture eventually forced her to quit her job.

In a New York Times article published last year, another woman describes working at a mine in the US where she endured sexist remarks, witnessed cellphones with pornographic pictures being passed around and had her drill and walkie talkie tampered with, threatening her safety. She also left her job.

In a LinkedIn article, ‘Anne B’ describes her experience, also in Canada, of inappropriate sexualised talk, being singled out and feeling unsafe when heading to the showers, which resulted in her feeling ‘disgust’ for the industry. She also decided to quit.

Another woman, Julie Kramer, went on Twitter to claim that she was fired at the beginning of the year from Hudbay Minerals’ Manitoba operation after reporting sexual harassment she experienced at work.

In July 2017, a camera was found in the washroom of Yellowknife RCMP Ekati Diamond Mine in Canada, and in Australia, the documentary Hotel Coolgardie shot in 2012 gives an insight into the raging machismo that fuels sexual harassment of women in a remote mining town.

One of the most shocking stories, however, is that of miner Binky Mosiane in South Africa. The young mother was raped and murdered underground at Anglo Platinum’s Khomanani mine in 2012. It took two years to convict her killer.

There have been very few studies done to quantify the scale of abuse women face in the mining industry

Male miners greatly outnumber female miners, increasing the potential for high-pressure situations. Credit: DmyTo/Shutterstock.

A lot of policies are not clear; they just say file a report

A culture of silence

Reading these stories, it seems apparent that a toxic culture of male chauvinism has manifested itself in many mining environments, resulting in a pack mentality that is protected by a wall of silence.

A major focus for the #MeTooMining campaign, says Lomas, will be to help men overcome what she terms ‘bystander behaviour’, which stops them speaking up when they witness aggressive and abusive behaviour.

Lomas has heard haunting stories from men, she says, about incidents they’ve witnessed and how bad they feel about not doing anything at the time because they felt helpless and outnumbered. “They didn’t have the support to say anything,” she says.

This campaign intends to give guidance to men on what they can do to help their female colleagues, as well as advocate for company training. “Men can create some distraction to break-up the scene, get the woman out of there, talk to her, give her support and bear witness to what happened if she does report it,” she explains.

The fledgling association is currently being organised internally but eventually Lomas wants to start campaigning for better reporting guidance, whistle-blower advice and independent support for women who make a complaint. Many of the procedures in place today, she feels, are not well thought out.

“A lot of policies are not clear; they just say file a report. But what happens when they do? Is the woman protected? Are they safe? Are they reporting to the immediate supervisor? What if he is actively involved in the situation? What if officers of the company and members of the board are involved, what are your options at that point?” she asks.

Women or men should go to their employers, she says, and find out what their policies are. If it is not sufficient, approach them and ask for improvements. Equally, if an office has good practices, Lomas wants to hear about it.

Women miners often have standard issue uniforms and PPE, which are ill-fitting and so ineffective and cumbersome.

A lot of policies are not clear; they just say file a report

Halting the revolving door

Canada is the perfect place to start a conversation about abuse in the mining sector as 75% of mining companies are registered in the country. But what reaction has she had to the campaign so far? “It’s not a landslide of people rushing out to say something, but people are engaging,” she says.

Is this perhaps to do with that culture of silence? “A lot of women I know have said, yes, we need this, definitely, and start telling me all these horrible stories, but then they explain it is too risky for them to come out and report it because there are so few of us [women], they are scared of losing their jobs.”

She refers to other male dominated industries, such as the financial sector, where very few women come forward and report sexual harassment. “It is your career that you feel you are putting at risk,” she adds.

Through her long career did she ever feel like leaving the sector, as some women do? “Absolutely. But there were times I felt that by just staying, by my mere presence, that I could impact the environment I was in, the company and project site, if I just kept to the work.”

Unfortunately, so many women don’t stay and more than just lip service must be paid to problems of sexual harassment and abuse in the industry if the mining sector truly wants to encourage more women to join. Otherwise, as Lomas concludes: “We can encourage inclusion and diversity, but unless we change the culture it is going to be a revolving door.”

Unless we change the culture it is going to be a revolving door