POST-PRODUCTION

Aftercare in the community, and the next chapter of Jabiru

In the Northern Territory, the Ranger uranium mine refined its last ore in January 2021. While rehabilitation work continues, the nearby town of Jabiru works to move on from mining. Matt Farmer asks: what does a mining community mean when the mine leaves town?

F

rom a distance, the Ranger Mine in the Northern Territory (NT) of Australia seems remote and isolated. Distance is one of two things the area has in abundance. For the next 100km in any direction, most of the residents are crocodiles.

The other abundant resource is uranium oxide, which Energy Resources Australia (ERA) has extracted at the site since 1980. In January 2021, the company refined the last of its stockpile, machines fell silent, and clean-up operations began.

The obviously remote location has led scammers to use the mine as part of a trick, claiming its poor phone signal prohibits from them speaking to victims. On its website, ERA states: “For the record, the Ranger mine has full internet and mobile phone connectivity despite its remote location.”

These utilities extend to the town of Jabiru, 5km west of the mine. As it closes, the town’s 1,100 population will transition their power supplies, their economy, and their livelihoods away from mining. These are the challenges for Jabiru, NT.

From mine power to a mini energy transition

The Northern Territory government committed A$135.5m to ensure the stability of Jabiru in the long term. As part of this, it called for expressions of interest for powering the town in November 2019.

Before this, residents relied on power from the mine, which used diesel generators. Applicants for the new system would have to use ‘at least 50%’ renewable energy, in line with local legislative targets. The state government expected a ‘strong market interest from both the renewable energy and utilities sectors’. EDL Energy won the contract with a hybrid system, fuelled by diesel and photovoltaic solar cells.

An EDL spokesperson says: “When considering energy sources for the project, solar was the most abundant of the renewable sources available in the region. Trucked diesel was selected as the thermal component as there are no gas pipelines in close proximity.

EDL designed the Jabiru Hybrid Renewable Project to ensure that at least 50% of annual generation comes from renewable sources.

“The cost of fuel in remote locations is always a major consideration, particularly where it is trucked in, which is the case at Jabiru. By installing renewable generation, EDL is able to lower the overall cost of energy for our customers and reduce carbon emissions, without sacrificing power quality or reliability.

“EDL designed the Jabiru Hybrid Renewable Project to ensure that at least 50% of annual generation comes from renewable sources. Our configuration represents the optimal mix of reliability and cost, while achieving a high renewable energy and low carbon outcome.”

The company often uses modular power designs for its power plants, so future expansion or changes can be made more easily.

Contractor Juwi Renewable Energy will install a 4.5MW diesel power station before the end of 2021. In early 2022, it will complete work on a 3.9MW solar farm, connected to a 3MW/5MWh battery storage facility. This will mark the German company’s sixth project.

// Artist's impression of the power project. Credit: EDL

Moving on from mining, Jabiru seeks new industry

When a community adopts a mine, it becomes folded into the pre-existing identity of the area. When a mine creates a community, it becomes a key focus of the area’s identity. A mine creates a visible population reliant on one business for their livelihoods. In Jabiru, the time has come for the mine to leave town.

The remains of the Ranger Mine cover 79km², described by ERA as “surrounded by, but separate from, the World Heritage-listed Kakadu National Park”. Kakadu covers approximately 20,000 km², including several communities of the indigenous Australian owners of the land, the Mirarr.

// Jabiru. Credit: Google Maps

Indigenous Australians have lived in the area continuously for approximately 65,000 years, and play a key role in the governance of Kakadu. The park also provides a relatively luscious home to one-third of Australia’s bird species, such as kookaburras and kingfishers, and around 10,000 crocodiles.

A few miles north-west of the town, tourists go croc spotting at the East Crocodile River. The town’s largest reptile is its hotel, which is shaped like a crocodile and can provide rooms for up to 250 humans.

The decline of tourism

In any other year, the park would attract just under 200,000 visitors. Authorities hope to grow this to 275,000 visitors over the next decade, and Jabiru residents hope tourism can feed the town.

The town has plenty of facilities, including sports clubs, a gallery, and several shops. The closest city is Darwin, 250km west. In between, Kakadu draws visitors to natural infinity pools at the top of waterfalls, and rock art painted onto ancient stones.

But the park has its own problems, causing indigenous Australian park managers to clash with Parks Australia. Several features have closed to the public, with delays of more than a year to their reopening.

In the eyes of foreign tour operators, this has made the park a less reliable attraction, and visitors have declined. Foreign tourists used to make up half of all visitors, but in 2019 they made up 17%. With Covid-19 preventing foreign tourism from everywhere but New Zealand, this can only decrease.

I would not be putting all my eggs in the tourism basket, I can tell you that.

This has given doubts to Jabiru residents over the plans. One resident told ABC: “I would not be putting all my eggs in the tourism basket, I can tell you that. A lot more effort needs to be put into the health of our people, the education of our people, employment of our people. […] Tourism is not the be-all and end-all.”

In some ways, park leaders now have no choice but to shape up. When royalty payments from the mine end, the 19 indigenous clans of the area will rely entirely on tourism. Unlike Jabiru, there is no chance of their residents moving on.

// 3D System Model and Completed Installation. Credit: Deimos

Who pays to transition Jabiru?

The funds from the Northern Territory government also intend to create new business, retail, and Aboriginal centres in the town. The money will maintain air access via the existing landing strip, improve education and health, and maintain current levels of public services.

While the local government has committed funds to Jabiru’s transition, federal funds have moved much more slowly. Two years ago, the Australian Government allocated A$216.2m to developing the park. This would include facilities in Jabiru, road improvements, and a new visitors centre. That pledge has since grown to A$276m, despite the pandemic. So far, A$5.4m of this has been delivered.

Kakadu hasn't had a lot of investment in the last 40 years and tourism has shifted over that time too.

Northern Territory governing coalition senator Sam McMahon said the area is ‘probably going to stagnate’ if the lack of funding continues. She told ABC: "Kakadu is fantastic but it's also tired. It hasn't had a lot of investment in the last 40 years and tourism has shifted over that time too.

“Whereas tourists were once happy to come and go on a cruise and see a croc and look at the natural beauty, tourists now are wanting much more interactive experiences."

She is not alone in this criticism, as Northern Territory’s tourism and Aboriginal affairs ministers have also asked the central government to fast-track their funding.

Tourism minister Natasha Fyles said: "This investment will result in improvements for traditional owners, greater certainty to tourism operators, and extended visitor access to Kakadu National Park and its tourism attractions.”

Community commitments

Certainty is what Jabiru residents seek, above all. ERA has contributed to the town’s development through its Community Fund, but this disappeared at the end of 2020. Owner Rio Tinto emphasises its work with communities and indigenous Australians, but the company has also faced criticism for destroying ancient Aboriginal sites in pursuit of iron ore.

Outside of this, the company prides itself on spending A$60.7m on voluntary commitments to community needs and social risks around its worldwide projects. While mining communities are entitled to public money, it is often private funds that hold the most meaning to them.

But transitions cost, and state funds allocated to Jabiru vastly outweigh those donated by Rio Tinto worldwide, ever.

In the end, the mine site will return to the park, and the Mirarr original owners of the land. Representatives of the indigenous Australian community have worked with ERA throughout the mine’s lifespan, and continue to consult with them during clean-up operations.

These end in January 2026, when replanting work aims to have finished making the area indistinguishable from the surrounding park.

The aim is that Kakadu Native Plants will remain a sustainable, ongoing local indigenous business.

Local seeds will plant up the mine site, where dredging work recently finished. A Jabiru business, Kakadu Native Plants, worked with ERA to decide species and collect seeds to grow in the area.

An ERA spokesperson wrote: “The aim is that Kakadu Native Plants will remain a sustainable, ongoing local indigenous business that will strive well beyond the mine closure. […] The journey to the rehabilitation of Ranger Mine Area is a journey we take together and in consultation.”

For Jabiru, the journey has only just begun.

Energy Resources Australia and Rio Tinto did not respond to requests for comment.

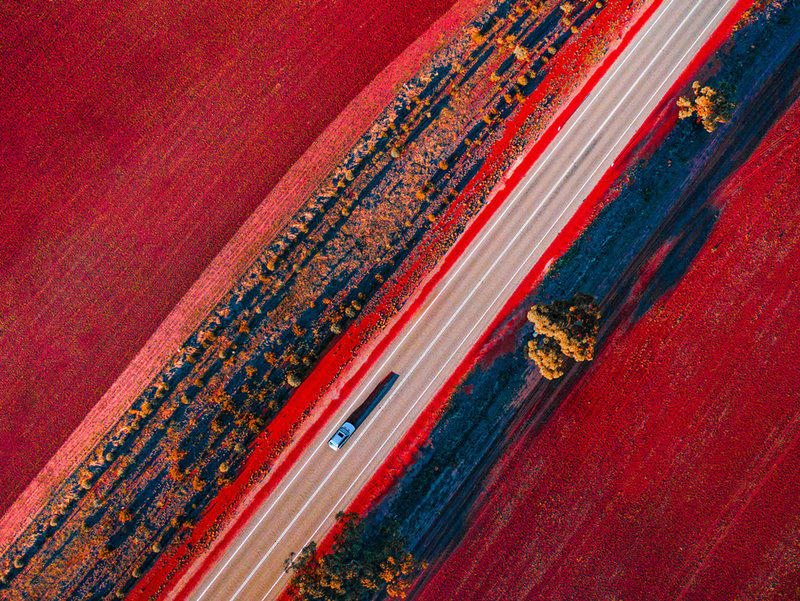

// Main image credit: ChameleonsEye / Shutterstock.com