Lobbying

The past, present and future of the Queensland Resource Council

Rio Tinto has announced plans to leave the influential Queensland Resource Council. Giles Crosse looks into the council’s history, and what the move might mean for the future of the lobbying group.

T

he Queensland Resources Council (QRC) is a lobbying group that has represented miners’ interests in the Australian state for years. A not-for-profit industry association, it represents the commercial developers of Queensland’s minerals and energy resources, and includes some of the industry’s biggest players, including Anglo American and Mitsubishi.

Yet Rio Tinto, a cornerstone of the global mining industry, has announced it is leaving the QRC. Rio Tinto chief executive, Australia, Kellie Parker, announced that, “after careful consideration, Rio Tinto will not renew its membership with the Queensland Resources Council for the 2022-2023 financial year.

“We have strongly valued Ian Macfarlane’s leadership and the support provided by the QRC to our Weipa bauxite operation. We also appreciate the QRC’s advocacy for our industry so we could continue to operate during the challenging Covid-19 pandemic.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this is something of a non-statement. It doesn't truly reveal what has taken place behind the scenes, nor what has driven the change. David Outhwaite, principal advisor for media relations at Rio Tinto, dodged offering further insight, writing, “I’m afraid that is all we are saying on the matter", in an email.

Decades of influence

Explaining Rio Tinto’s departure from the group can be challenging, considering the influence the WRC has held over Australian mining for close to two decades. The council was formed in November 2003, succeeding the Queensland Mining Council, and argues that the mining, exploration and oil and gas industries are the mainstay of the Queensland economy and significant contributors to the economic wellbeing of Australia.

Back in 2003, sustainability was less prevalent in the corporate world, and the resource-intensive identity of the QRC is somewhat at odds with more modern initiatives to reduce the environmental damage of big industry.

Today, the QRC and its members promise they are “committed to working together to achieve energy security while taking proactive steps towards a low emissions economy … Our industry makes a major socioeconomic contribution to Queensland and we have an important contribution to addressing energy and climate change issues while continuing to deliver value for our shareholders and stakeholders alike".

The QRC has often implemented this policy through political lobbying. The council assesses both governance and advocacy performance annually, and, notably, its QRC Political Engagement Policy recognises that one of its core activities is to advocate for and influence policy outcomes that are in the ”best interest” of the Queensland resources industry.

Our industry makes a major socioeconomic contribution to Queensland and we have an important contribution to addressing energy and climate change issues.

QRC's latest release highlights the importance of the Queensland resources sector to the national economy. The report shows that the minerals and energy sector contributed $27.4bn (A$38.6bn) in direct spending to the state economy in 2020/21, a 2.1% increase year-on-year.

QRC chief executive Ian Macfarlane said that the latest Resources and Energy Quarterly report showed commodity exports – including Queensland’s strengths of coal, bauxite, copper and zinc – were all performing strongly. Coal joined iron ore as only the second Australian commodity to break the $69.6bn (A$100bn) export mark.

“Queensland’s resources and energy commodities are the powerhouse that is driving both the state’s economy and the national economy,” Mr Macfarlane said. “Our commodity exports reinforce our role as a trusted international partner, especially to support energy security in Europe.

“These sky-high export values also strengthen Australia’s national security by delivering jobs and economic returns and encouraging new investments in the resources projects that will keep Australia strong in the years ahead, including renewables, critical minerals and hydrogen.”

Clean energy, unclear commitments

Green tech does get a mention, albeit following the top-level stance on utilising finite resources first, suggesting that the clean energy agenda may not be at the top of the council’s priorities.

Indeed, in December 2021, the QRC wrote about tougher legal consequences for environmental protestors, notably activists who stop trains from hauling coal to port, saying this costs the state taxpayer about $2.4m (A$3.4m) a day.

“Right now, Queensland needs all the revenue it can get to deal with the ongoing, economic impact of Covid-19, which is unfortunately a long way from being over,” said QRC chief executive Ian Macfarlane.

“Right now, Queensland needs all the revenue it can get to deal with the ongoing, economic impact of Covid-19.

“People who choose to lock themselves onto rail lines and port equipment and climb onto coal wagons are not harmless, and their actions come at a huge cost to individual companies and to Queensland.”

In November 2021, the QRC said that Queensland’s resources sector will consolidate and build its role as the state’s economic powerhouse over the next decade, as companies rapidly incorporate renewable energy, energy storage and low-emission technologies into their operations.

But in the detail, Macfarlane highlighted: “Our industry’s largest contributor to the state economy by commodity is coal, which makes up 70% of our $59.8bn (A$84.3bn) contribution, followed by metals at 16% and oil and gas at 11%, with other contributions like electricity generation, silica and kerogen making up the balance."

Not a word on renewables, and by those percentages there remains little space for them either.

Our industry’s largest contributor to the state economy by commodity is coal, which makes up 70% of our $59.8bn contribution.

However, he did say a “unique mix” of resources could work: “Queensland has substantial deposits of coal, gas and minerals which will be increasingly essential in the production of green technologies and products such as electric vehicles, batteries, wind towers, solar panels and a range of electronics.

“We also have deposits of in-demand critical minerals, particularly in the state’s north, that are being used in the latest defence, medical and renewable energy technologies.”

Macfarlane also said in November 2021 that a new $710m (A$1bn) Low Emissions Technology Commercialisation Fund will help secure the long-term future of the state’s $58.6bn (A$82.6bn) resources sector.

// 3D System Model and Completed Installation. Credit: Deimos

A changing industry

Assuming that Rio Tinto's departure from the QRC is purely based on QRC lobbying, more sophisticated explanations, to a degree, shine through. The QRC does talk about net zero, low emissions and climate change, but it rarely, if ever, strategically prioritises these ends over extracting every ounce of Queensland's fossil resource.

Macfarlane is a candid operator too. His words on protesting coal don't sit too well with more modern, balanced positions that suit environmental and social governance or corporate social responsibility reporting better, both elements that increasingly dominate annual meetings for the world's mining majors.

At a push, it could be argued the very nature of the QRC seems a little outdated. Its stance seems tacitly pro-fossils and profit and its positioning isn't as balanced as it could be. But it's worth noting the QRC released an updated Energy and Climate Change and Political Engagement Policy in March this year.

// Main image: 3D System Model and Completed Installation. Credit: Deimos

An orderly transition to a low-emissions economy will require an integrated set of national policies, which are technology-neutral.

“The Queensland Resources Council and its members are committed to working together to achieve energy security while taking proactive steps towards a low-emissions economy,” reads the report. “An orderly transition to a low-emissions economy will require an integrated set of national policies, which are technology-neutral.”

Indeed, the QRC supports the Paris Agreement and its emissions reductions goals to limit global warming to well below 2oC, preferably to 1.5oC, compared to pre-industrial levels.

So what went on behind the scenes to spark Rio Tinto's departure, itself a firm not unfamiliar with contentious elements of resource extraction and therefore wary of antagonism in that space? These secrets may never be revealed, but the move points to a growing wave of environmental consciousness, if not action, within the mining industry.

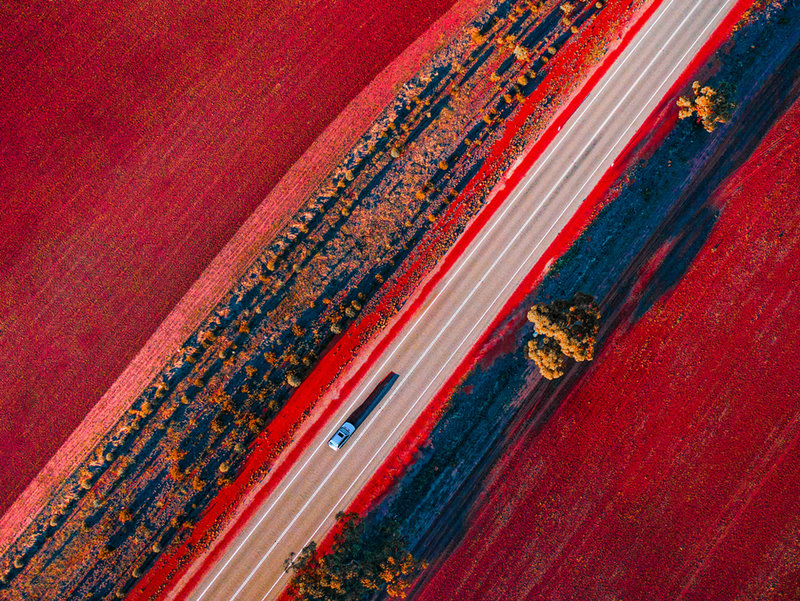

// Main image: Quarry in Mackay, Queensland. Credit: Jackson Stock Photography / Shutterstock