Weather

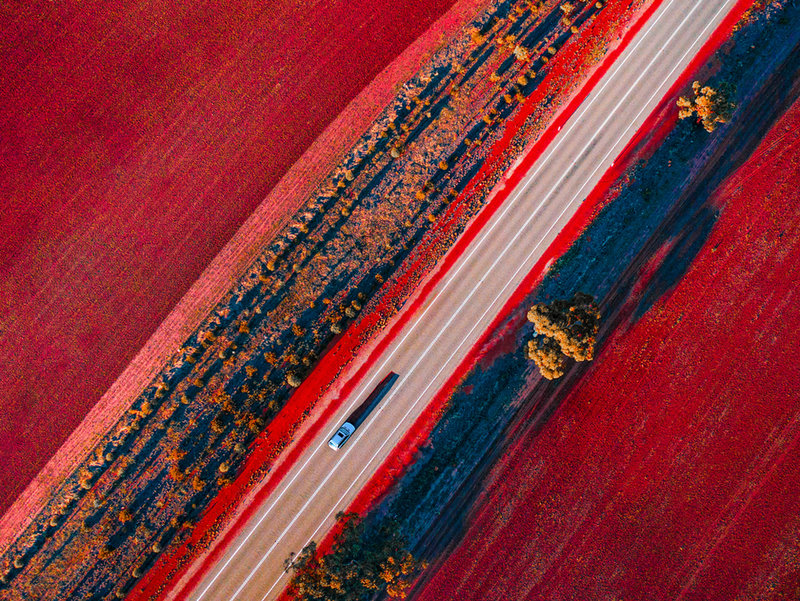

Climate change, Australian mining, and the storm ahead

The science is clear: with years of emissions locked in, Matt Farmer explores how Australia will experience climate change through its increasingly extreme weather.

C

limate change and its direct impacts will increasingly define this century, and work within it. Changing weather patterns will ultimately lead to changing work practices, especially in the unwelcoming outback and its many mining operations.

Miners must now face up to a raft of small concerns that will together change how business functions. Climate models give some insight into how the environment might change, but they cannot spell out the numerous measures that companies will need to take in order to navigate the, literally, stormier seas ahead.

So, how will global warming and future weather affect mining in Australia?

What to expect

Data from the Australian Government’s Bureau of Meteorology shows the expected heat rise over the next 20 years. This temperature change seems the most pertinent challenge, but it will cause a range of more direct impacts to miners.

Australia’s Construction Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU) national research director Peter Colley says: “Mining in Australia generally takes place under adverse conditions already, so there is already a practice of designing operations to cope with that adversity. However, global warming will undoubtedly increase the intensity of the problems.

“Mining in Australia generally takes place in harsh and remote locations – generally very dry and subject to temperature extremes. These same locations are already subject to a ‘cyclone season’, at least in the northern half of Australia, and all are subject to occasional flooding and bushfires. The infrastructure that services mines – notably railways, roads, and power lines – is also subject to these extremes of nature.

In its 2021-22 severe weather outlook for the coming year, the bureau warned of a likely above-average cyclone season. The next season falls on a La Niña year, with warmer seas encouraging more extreme weather. But as climate change causes seas to warm consistently, the frequency and intensity of cyclones will increase correspondingly. This threatens onshore damage, but will have the greatest effect at sea, disrupting shipping and supply chains.

A glimpse at fires yet to come

During the disastrous 2019-2020 wildfire season, much of the south-east and north of the country burned, with ramifications across the country. Climate scientists later said that climate change had worsened the risk and increased the severity of fires, which returned the following year.

Local ecosystems require limited amounts of burning to stay healthy, but with every passing year, fires grow more difficult to control. Climate change will cause fire season to start earlier, last longer, and burn more severely across a greater area.

Operations could be constrained further […] if air quality continues to deteriorate.

In the 2020 fires, BHP announced a fall in production when smoke plumes damaged air quality at its Mount Arthur site. In its financial results at the time, the company stated that “operations could be constrained further […] if air quality continues to deteriorate”. Aside from air quality, some BHP workers took leave to work as volunteer firefighters or to protect their homes.

Ultimately, Covid-19 constrained these operations anyway, but future fires may mean poorer production as fallout from climate change. More frequent fires will mean more frequent evacuations, greater displacement of workers, and more time lost.

Greater regulation around machinery and water?

Mining operations themselves present a risk of ignition. If Australia goes in the direction of California, authorities may look to increase regulation around potential ignition sources. This may mean changes to equipment such as generators, but also to worker transport and site power transmission. However, studies in the US have found that human activity rarely causes wildfires, with lightning still the leading cause.

Fires also intensify scrutiny on water sources used in firefighting, and the water consumed and polluted by mining operations. During the 2019 fires, a report warned that mining operations removed eight million litres of Sydney’s drinking water per day. This came at a time when reservoirs sat half empty, with some mines warning they could run out of water entirely. This possibility will also become increasingly likely, as hotter weather devastates the water cycle.

The report made 50 suggestions as to how mining projects could save water for a drier future, including causing mining companies to purchase the water effectively removed from the water cycle by mining operations. It also suggested a range of measures to decrease the amount of water used in operations.

Under the duty of care, I expect that mining companies will have to gradually update their operating procedures to reflect increasing extreme weather.

While legislators will likely change their priorities as global climate action intensifies, unions believe that companies have an obligation to change under existing laws.

CFMEU’s Colley said: “Mining is covered by both specific mining safety legislation to address particular systemic and catastrophic risks, and broader OHS law that imposes a general ‘duty of care’ on a site operator to look after the safety of all those on site.

“Under the duty of care, I expect that mining companies will have to gradually update their operating procedures to reflect increasing extreme weather.”

While weather may grow wetter and stormier, the amount of water available on the ground will likely decrease. Hotter air holds more water within it, which in turn presents a new threat of lethal “wet bulb” temperatures.

The danger of lethal wet-bulb temperatures

Global warming will increase temperatures in most areas of the world, pushing them toward a dangerous threshold for work. Employers would usually remedy this with increased downtime, better hydration, and better ventilation. However, climate change will also remove these options.

Humans naturally lose heat via the evaporation of sweat, but beyond a certain humidity, this becomes impossible. In these humid conditions, regardless of wind, shade, or hydration, people naturally acquire heat from their surroundings until they overheat. In this environment, cooling down only becomes possible in drier air, usually provided by air conditioning.

Climatologists use “wet-bulb” temperatures to factor humidity into climate data and predictions. Currently, even the hottest weather produces wet-bulb temperatures just above 20°C in the country’s largest cities. Wet-bulb temperatures of more than 35°C always risk human health, regardless of any conventional cooling method. Lower temperatures can present equal risk in less ideal conditions, such as in sun exposure or on a still day.

“We expect an already tough job to become tougher”

Over isolated periods, these temperatures present the risk of heatstroke, but in the long-term they will make areas entirely uninhabitable. In at least two areas of the world, conditions have briefly exceeded this threshold. As global warming progresses, more places will exceed the threshold more often, with some areas of Australia soon to follow.

Areas of Western Australia, such as the country’s largest iron ore terminal in Port Hedland, have already come close to lethal wet bulb temperatures. The mineral-rich Pilbara is among the least humid areas of the country, but it lies across an area expected to see the greatest temperature rise. If Australian mining companies want to continue work in a more uninhabitable environment, they must soon adapt to do so.

We expect there will be more days with temperature extremes that may cause work to cease and equipment to fail.

Colley said: “The union expects an already tough job to become tougher. While air-conditioning is standard equipment in the open cut/open cast environment, there are plenty of work situations where air-conditioning is not possible.

“We expect there will be more days with temperature extremes that may cause work to cease and equipment to fail. And more occasions when work and production will cease or be reduced due to major events like cyclones, floods, and bushfires. We think mining infrastructure will come under more pressure and in some cases have to be rebuilt to operate under greater extremes.”

// Main image: Teralba, NSW/Australia - October 24, 2012: Fireman or firefighter backburning and extinguishing a wildfire grass and bushfire. Editorial action in landscape format. Credit: Jordon Sharp / Shutterstock.com