Environment

A perilous precedent: inside New South Wales’s environmental offsets scheme

Reports that coal companies have been allowed to delay environmental offsets on both new and expanding mines in New South Wales for up to ten years have outraged environmentalists, and undermined efforts to diversify Australia’s economy away from fossil fuels. Julian Turner reports.

C

ould Glasgow be the setting for the latest offensive in Australia’s highly publicised ‘climate wars’?

Debate over the country’s response – or the lack of it – to the climate change emergency has raged for decades. High-profile casualties include former premier Malcolm Turnbull, whose attempts to address years of inaction led to his downfall – twice. As recently as last June, deputy prime minister Michael McCormack was replaced following a revolt over environmental policy within his own party.

Current Prime Minister Scott Morrison arrived for the COP26 summit having committed Australia to a target of net-zero emissions by 2050, but at the time of writing, he has yet to announce any new policies or legislation to achieve it, leading to criticism from environmentalists and academics.

Morrison’s situation has been made even trickier after reports emerged that offsetting schemes in the eastern state of New South Wales (NSW) have been delayed for years because governments have allowed mining companies there to push back deadlines for protecting sites for conservation.

The subject of sustainability in Australia has once again made headlines after an investigation by The Guardian Australia alleges that at least nine coalmines in NSW, including several in the Hunter Valley, received special permission from federal and state regulators on multiple occasions that allowed them to avoid penalties for not securing permanent protection of habitat.

The Guardian investigation led to an ongoing parliamentary inquiry into NSW’s use of environmental offsets, with upper house environment and planning committee chair Cate Faehrmann quoted as saying that there had been “a disturbing lack of transparency around sites protected as offsets”.

How do environmental offsets work?

The theory is similar to the practice of carbon offsetting, intended to compensate for a company’s or individual’s emissions by funding an equivalent CO2 saving elsewhere.

Biodiversity offsetting uses environmental values gained at an offset site – where native vegetation and threatened species are protected and managed in perpetuity through actions such as fencing, weed and pest control and planting native species – to compensate for biodiversity lost to development, including mining, at another location.

The primary purpose of offsetting is to ensure development projects are sustainable and do not have unacceptable impacts on native ecosystems and species. Offsetting also incentivises the protection of biodiversity on private land, as well as providing an income for landholders that own offset sites.

However, in a submission to the parliamentary inquiry in August, industry association the NSW Minerals Council stated: “While the government’s intention to provide an income stream for landholders and farmers by making private conservation land the central source of offset supply is admirable, it has not been able to deliver supply required by the market.”

While the government’s intention to provide an income stream for landholders and farmers … it has not been able to deliver supply required by the market.

Likewise, the government’s efforts to set up thriving and liquid biodiversity offsets market has not materialised and has significant barriers to success that are not being addressed, the council said.

According to the NSW Government, its Biodiversity Offsets Scheme uses “a transparent, consistent and scientific approach to assessing biodiversity values and offsetting the impacts of development on biodiversity”. This is achieved using two instruments: credit obligations and biodiversity credits.

The former is a legal-binding agreement signed by a developer that obligates them to compensate a landholder for unavoidable biodiversity impacts resulting from development or vegetation clearing.

Developers can do this by purchasing ‘like for like’ credits in the market; developing a stewardship agreement with NSW Government to meet the credit requirements; or using an offsets payment calculator to determine the credit obligation cost and paying that amount into a government fund.

In the biodiversity credits system, landholders establish a biodiversity stewardship site on their land, and receive annual payments to run it. The stewardship site then generates credits that can be sold on to developers or landholders who require those credits in order to offset activities at other sites.

The offsetting controversy in NSW explained

Activists argue that the environmental protection system in NSW is “fundamentally broken’, and that mining companies there continue to exploit loopholes in the rules in order to avoid penalties.

The nine NSW mines identified by The Guardian Australia are: Ulan (most of Ulan’s required offsets are now protected permanently, but ten hectares remain outstanding); Mount Thorley Warkworth; Bengalla; Mount Pleasant; Mount Owen; Boggabri; Mount Arthur; Werris Creek; and Maules Creek.

Kim Garratt, an investigator with the Australian Conservation Foundation, told the Guardian that the pattern of delays had set a precedent “for mining companies securing offsets only when it’s convenient for them, apparently without consequences”.

“Offsets facilitate environmental destruction while kicking the claimed compensatory measures down the road,” Garratt said. “The worst thing about these examples is that they are not unusual in any way – it is par for the course that big, billion-dollar coal companies are granted almost infinite extensions to the timeline for securing offsets.

Offsets facilitate environmental destruction while kicking the claimed compensatory measures down the road.

“Regardless of who is to blame for any specific offset being delayed, the fact is that until these habitats are legally protected, the company can walk away from their commitment tomorrow.”

In response, representatives from the mining industry in NSW argue that there have been delays in arrangements for some sites, and this is largely due to significant changes to the process for securing offsets in the state. They also point out that these sites are owned by the mining company and are already being managed for conservation as required by the project approval and management plans.

The mining companies told The Guardian Australia that many of their required offsets had been identified and managed for conservation since the commencement of their projects. They blamed changes to state conservation legislation, bureaucratic backlogs in NSW and disagreement between the state and federal governments over what legal mechanism to use to conserve a site for the delay in securing the required permanent protection.

In its inquiry submission, the NSW Minerals Council also underlines the importance of the sector to the state economy. In 2019–20, mining companies directly spent an estimated $14.9bn in the NSW economy, including $2.7bn in wages and salaries, and $1.9bn in state government payments. According to Council figures, the industry in NSW employs 28,780 full-time equivalent workers.

A clean break: the energy transition in Australia

However, if operators were allowed to escape their environmental obligations under the offsetting scheme, this casts doubt not only on the legitimacy of legal measures designed to protect the NSW environment, but also Australian authorities’ perceived commitment to the clean energy transition.

This received a further blow in April 2021, when another Guardian report alleged that environmental consultants from a company that advised governments on major developments in NSW had made windfall gains of more than $40m by selling conservation offsets for those developments to the state and federal governments. Two NSW Government departments have launched internal investigations.

We are on course to fundamentally transform our electricity sector broadly in line with net zero.

Irrespective of these setbacks and the current stalemate over a national net-zero target, Australia’s power sector is steaming ahead with its transition, says Tennant Reed, head of climate, energy and environment policy at the Australian Industry Group. “We are on course to fundamentally transform our electricity sector broadly in line with net zero,” he told Energy Monitor in August.

Attention now turns to Glasgow to see if Prime Minister Scott Morrison can take advantage of this momentum, transcend internecine feuds in his coalition government, and use COP26 as a platform to unveil definite net-zero policies.

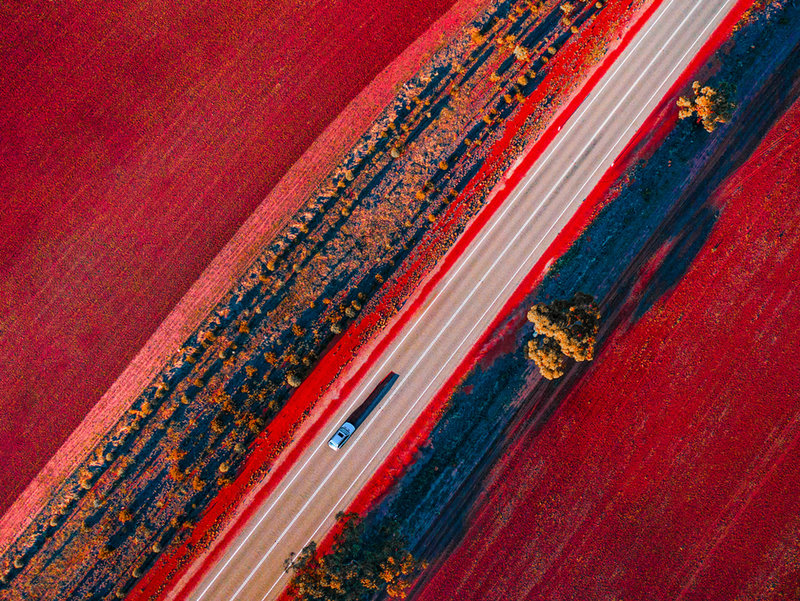

// Main image: Peak Hill, NSW, Australia - Jan 18, 2021: Abandoned Open Cut Gold Mine. Credit: Alex Cimbal / Shutterstock.com

// 3D System Model and Completed Installation. Credit: Deimos