FRAUD

How not to lose $36m in a copper trade scam

Earlier this year, a pair of commodities traders became embroiled in a legal dispute after what was supposed to be $36m of copper turned out to be painted paving stones. Matt Farmer explains what happened and how those in the commodities industry can avoid a repeat.

S

o, here’s the story: after purchasing 6,000 tons of blister copper, commodities trader Mercuria arranged for shipment to China. The seller, Turkish trader Bietsan, organised shipment and insurance from Istanbul. As the 300 containers left Turkey, Mercuria paid for the copper over five instalments in August 2020.

In the same month, the shipments began arriving in China. Their recipients found them to contain only paving stones, spray-painted with a copper colour. This would usually count as a non-delivery, covered by the shipment’s insurance. However, Mercuria alleged that six of the seven insurance contracts provided by Bietsan were forged.

Turkish police later arrested 13 suspects. In March 2021, these events came into public knowledge, causing a few smirks and chuckles at the traders’ expense. While this deal occurred between commodity traders, the scam exposed a vulnerability in metals shipping that mining companies regularly take for granted.

Avoiding scams and fraud in shipping

Businesses and consumers often overlook the complexities of international shipping, even as the industry rapidly grows. While the pandemic has caused a spike in consumer delivery crime, is the same true between businesses?

Global shipping follows regulations laid down by the International Chamber of Commerce’s (ICC) Incoterms. These lay out the format for trade documents, the process of making purchase orders, and what to expect when exporting.

The organisation introduced a new set of rules in 2020, though the previous 2010 terms remain in use. The ICC offers the full Incoterms in digital or physical copies, as well as training in their application.

The ICC has previously warned of fake versions of the Incoterms distributed online.

These may not apply to all exporters, but larger companies may benefit from their clarity on what the different rulesets mean in practice. This could be especially important, as the ICC has previously warned of fake versions of the Incoterms distributed online.

The Incoterms cover documents such as the bill of lading, which has its own scams associated with it. The bill of lading acts as a receipt for shipment, establishing a contract between the supplier and the shipper. It holds details of the supplier, the shipper, when goods changed hands, and details on the goods.

This document has become the centrepiece of several scams. Some companies issue multiple copies of a bill, collecting several payments for one cargo.

Sometimes, freight forwarding companies withhold the bill of lading, effectively saying the company never received the cargo. The shifty shipper may then expect a large, unforeseen 'fee' in order to issue the bill. Suppliers are obliged to pay this, as without the bill most insurance policies will be invalid.

Pop-up freight forwarders hiding online

Businesses are often lured to dodgy shippers by surprisingly low prices found online. Often, the relevant companies only exist online, shielding their owners from some of the consequences of bad business.

Doing business digitally also makes it easier for fraudsters to rebrand or restart their front with a new name. In doing so, they may simply keep whatever cargoes they have, offering no bill of lading at all.

Pop-up companies like these may look legitimate, but businesses should employ the same diligence as consumers when arranging shipping. Customer reviews and testimonies on external sites can give insight into a shipper’s record and age. As with all deals, if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

The importance of insurance

Insurance feels like an obvious solution. In the painted rocks scam, insurance documents for the shipment were found to be fake, leaving Mercuria exposed. Even when both sides are independently insured, one fault can invalidate another party’s contract.

Peter Flint, partner at international legal firm Volterra Fietta, explains: “Traders and their banks are reliant on the accuracy of seller or shipper documents, but these alone will not guarantee the provenance or origin of the commodity in every case. Forged or fraudulent documentation at the point of origin or shipment will likely invalidate the trader’s insurance unless expressly covered.

“Cargoes will commonly be inspected by a certified surveyor at the point of shipment, but this will not protect the trader in the event that the carrying vessel makes a call at an intermediary port at which the shipment is exchanged for the 'dummy' cargo. In these cases, the insurer may be obliged to indemnify the trader under its cover for cargo theft.”

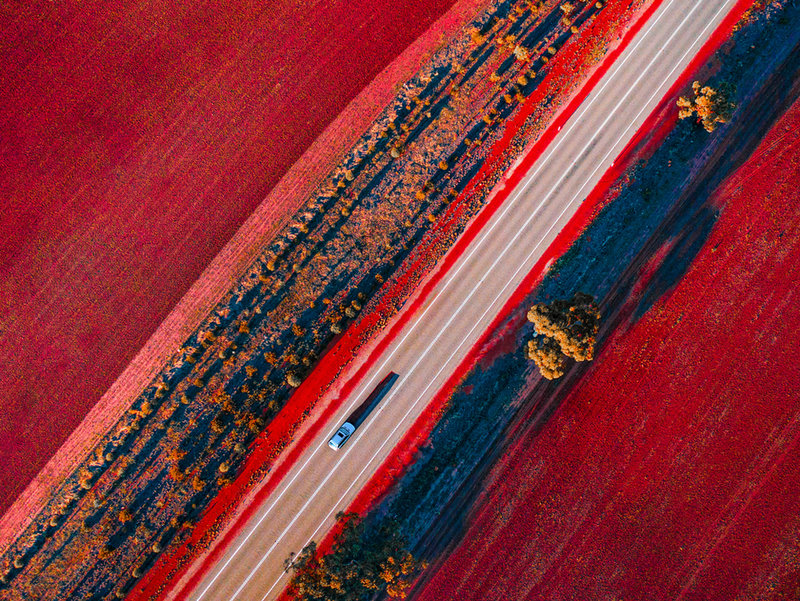

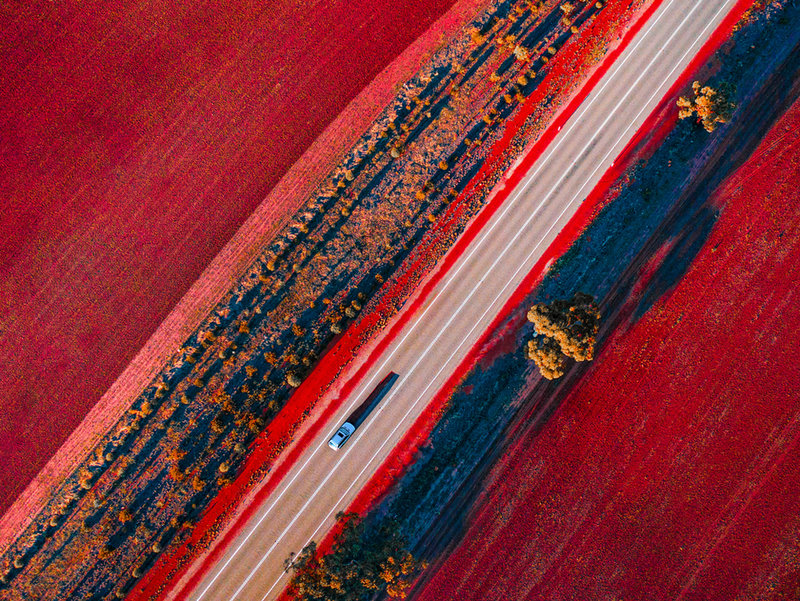

// Larger logistics companies, such as MSC or Maersk, offer their own packages of insurance. Credit: MSC

Shipments are generally sealed by port authorities using sturdy metal bars, labelled with an identifying number. In the case of the $36m copper theft, criminals replaced the broken seals with imitations, labelled with incorrect numbers.

Most trade scams do not involve organised criminals breaking into containers at night. In the Turkish incident, there is no reason to believe that the shipper colluded with criminals. Ultimately, criminals can only hit the targets they know of. Information can be a valuable resource, and keeping shipment details quiet in an online age poses a whole host of new problems for international trade.

Bietsan and Mercuria did not respond to requests for comment on this article.