PROJECTS

What is the state of Greenland's mining politics?

Australian miner Greenland Minerals has been planning the development of a rare earths mine in Greenland. However, after a left-wing political party’s victory in the Arctic island’s general elections threw the project into doubt, Yoana Cholteeva dives into the territory’s political situation to learn what comes next for the miner and its efforts.

G

reenland Minerals’ large-scale rare-earth project, known as Kvanefjeld or Kuannersuit, is deemed prolific enough to become the most significant producer of rare earths in the western world.

Situated at the unique Ilimaussaq Alkaline Complex in the semi-autonomous Danish territory of Greenland, with mineralisation enriched in rare earths, uranium, and zinc, the land has indicated the presence of over one billion tonnes of mineral resources to date.

Collectively, these factors have been estimated to make Kvanefjeld a globally significant supplier of rare earths for decades to come.

However, after liberal politician Múte Bourup Egede from the Inuit Ataqatigiit party gathered 37% of votes in the April elections, becoming prime minister, concerns arose that the uranium-opposing party might interfere with Greenland Minerals’ plans to develop the Kvanefjeld complex.

The previously ruling Democrat party recently withdrew from the governing coalition, leaving Inuit Ataqatigiit, along with the social democratic Siumut and separatist Nunatta Qitornai parties, as a minority. The remaining coalition parties are eyeing some changes.

The rising need for more rare earth minerals

At a time of trade tensions and increased regulation of the rare earth sector in China, Greenland was hoped to become a valued new source of rare earth elements. The minerals are particularly important to the growing magnet and catalyser industry that underlies many spheres, including the manufacturing of climate-friendly technologies.

According to Statista, global rare earth oxides demand for the production of magnets amounted to 43,733 metric tons in 2019 and is forecast to nearly double, to 82,469 metric tons, by 2025. Rare earth deposits in Greenland have also been evaluated as the world's biggest undeveloped deposits by the US Geological Survey.

At a time when many are looking to reduce their reliance on China’s mineral monopoly, the prospect that the Greenland mine might be closed down could interfere with the EU's long-term plan to source more rare earth metals in the region.

Earlier this year, Greenland Minerals confirmed that the status of its Kvanefjeld Project remained unchanged, as a statutory public consultation process was initiated by the Greenland Government on 1 June, which received an extension to 13 September.

Lawmakers and members of the national assembly requested changes to the public-consultation period due to concerns that Greenland’s Covid-19 restrictions would limit participation in the meetings.

This is all happening under the shadow of large-scale environmental disruption from the warming Arctic.

“We are still in a situation in which everyone has something to say and has an opinion about the project,” Greenland Mining Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen said in a statement.

“That is the point of the public comment process. No decision will be made until Naalakkersuisut [the government’s chief executive body] is sure that no stone remains unturned. Extending the comment period will make sure that is the case.”

Amid talks with Greenland's newly-formed government and the local opposition, Greenland Minerals said that it has sought legal advice, including over its right to be granted an exploration licence.

Boris Ivanov, founder and CEO of global mining group Emiral Resources, expressed his views about the collision between the Greenland state and international interests: “The public meetings, which will also include political representatives, are bound to be tumultuous and unearthly, a case where economics are pitted against ethics and local politics.

“This is all happening under the shadow of large-scale environmental disruption from the warming Arctic. We can be sure that global powers will be watching the unfolding situation carefully.”

Environmental concerns and political independence

As the Kvanefjeld project is planned to consist of a mine, refinery, and a concentrator, producing a mineral concentrate of 20%-25% rare earth oxide, the recent political changes in the country are raising questions over the likely consequences for the miner and the area’s rare earth prospects.

While Ataqatigiit still needs to form a coalition for a government majority, much of Greenland’s April elections revolved around the question over whether the island should allow an international firm to mine its rare earth deposits.

The main concern underlying the case is that radioactive uranium from the mine could leach into Greenland’s farmland and damage the environment, leading to Inuit Ataqatigiit’s pledge to block the project.

The Kvanefjeld project has indeed been a matter of concern since its planning stages, because of fears that radioactive dust could settle on the nearby town of Narsaq.

The environmental-impact assessment needs, in my opinion, to be redone. They haven’t done a good enough job.

In recent months, new discussion revolved around another radioactive element, thorium, that may remain on the site after the mine is dug, exposing the area to pollution of drinking water and fishing disruption.

In addition to this, local experts have also raised questions around Greenland Minerals’ calculations that the operations at Kvanefjeld would generate $240m for Greenland per year, or approximately a third of the annual subsidy the island receives from Denmark.

On a similar note, the country’s leading geologist has criticised the content of the 300-page report, put together by independent experts on behalf of Greenland Minerals, which has assessed the possible environmental concerns related to the mine.

“The environmental impact assessment needs, in my opinion, to be redone. They haven’t done a good enough job. There are too many unanswered questions,” Ole Christiansen, geological advisor for the Kujalleq region of Greenland, told newspaper AG.

Any mining project or investment must adhere to certain environmental standards and, specifically, shouldn’t bring radioactive substances above ground.

In response to the prevailing fears, Greenland Minerals said in April that uranium was of no great importance to its project, attempting to address the existing concerns.

While the situation surrounding Greenland Minerals, which has been operating in Greenland since 2007, remains entangled, the company currently still holds the licence for the project, having gained preliminary approval for it in 2020.

As the Inuit Ataqatigiit’s main objective appears to put the economy on a more resilient footing, so that the territory of Denmark can negotiate greater independence, a mineral boom could help support this and transform living standards.

Ivanov says: “However, any mining project or investment must adhere to certain environmental standards and, specifically, shouldn’t bring radioactive substances above ground.”

Local tensions and trade prospects

The election result putting Inuit Ataqatigiit to the foreground comes at a significant time for Greenland, after former US President Donald Trump offered to buy the territory from Denmark in 2019, as international mining firms eyed its promising mineral reserves.

The involvement of China’s rare-earth company Shenghe Resources, which owns a 10% stake in Greenland Minerals, has also escalated local tensions.

“These are entirely understandable challenges that have raised very legitimate concerns, so I understand the reasons for the opposition,” Dwayne Menezes, founder and managing director of the Polar Research and Policy Initiative think tank, told The Sydney Morning Herald.

The Greenland case demonstrates that the world’s long-term energy transition is being weighed against local concerns.

Menezes continued: “However, there is also the risk that if the operation were to be paused for an indefinite period, or shut down completely, it would send signals to the world that are counter-productive to what Inuit Ataqatigiit might actually want – that Inuit Ataqatigiit is against economic development in general, or that Greenland is now closed to mining.”

While the potential of Greenland’s domestic reserves has attracted serious attention, the idea of foreign companies interfering with the land and environment seem to provoke further opposition by the islanders.

“The Greenland case demonstrates that the world’s long-term energy transition is being weighed against local concerns. The ‘green revolution’ is certainly changing dynamics in global politics as well as alliances and trade flows, but also highlights the need for value chains to be sustainable and socially responsible,” Ivanov says.

Whether the parties involved will manage to join their priorities, agree on reasonable approaches to rare earths mining and the possible consequences of this exploration, remains to be seen.

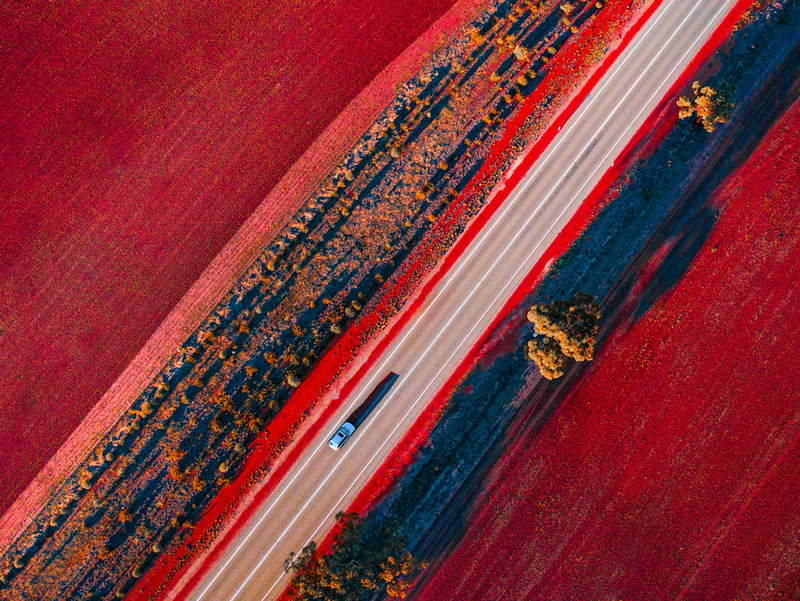

// Main image credit: Simon Pugsley / Shutterstock.com